[Webinar] How to Implement Data Contracts: A Shift Left to First-Class Data Products | Register Now

Building Transactional Systems Using Apache Kafka

Traditional relational database systems are ubiquitous in software systems. They are surrounded by a strong ecosystem of tools, such as object-relational mappers and schema migration helpers. Relational databases also provide strong guarantees in the form of ACID transactions, which are loved by developers for their all-or-nothing semantics.

Today’s businesses, however, want to process ever-increasing amounts of data. Write-heavy loads in particular may run into scalability issues in traditional relational databases and therefore need alternative architectures that scale to their needs. This article presents an event-based architecture that retains most transactional properties as provided by an RDBMS, while leveraging Apache Kafka® as a scalable and highly available single source of truth.

ACID? Say again?

ACID refers to Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability. What do these mean, exactly?

- Atomicity in relational databases ensures that a transaction either succeeds or fails as a whole. This is especially relevant if the transaction consists of multiple SQL statements.

- Consistency expresses the idea that the database is in a valid state. Martin Kleppmann argues in his book Designing Data-Intensive Applications that consistency is an application-specific notion. The database can only provide support by enforcing constraints, such as referential integrity. Defining the correct constraints and transactions is still up to the application.

- Isolation refers to transactions that can be processed without interfering with other transactions, for example, during concurrent processing. The database system guarantees that multiple concurrent transactions will appear to the user to be executed one after the other. If two conflicting transactions modify the same entity, one of them will be successful and the other will fail.

- Durability guarantees that the results are persisted after a successful commit. All of these are enforced by relational databases. Upholding each property in a system based on Kafka is tricky but not impossible, as you are about to find out.

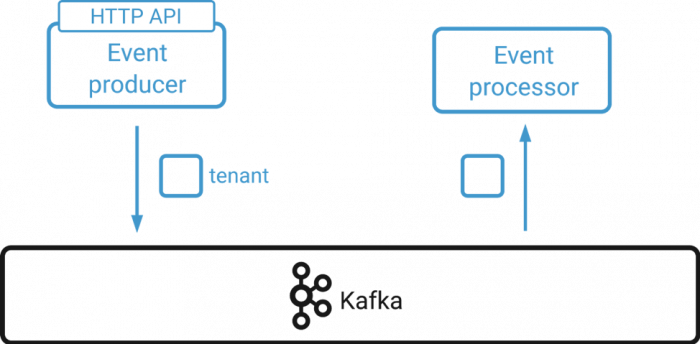

A simple multi-tenant system

Let’s assume we want to build a multi-tenant system. Each tenant has a unique fixed identifier as well as other miscellaneous data, such as contact details or billing address. In order to add, modify, or delete a tenant, an administrator can interact with the system via an HTTP API. The event streaming model lends itself to an event-based architecture, so Kafka serves as a central event hub. All API calls are transformed into events and written to a Kafka topic using the tenant identifier as key and the remaining data as value.

If an event consumer encounters a new tenant identifier, it will create a new tenant. Subsequent events with the same key are considered modifications to the tenant, and tombstones represent tenant deletions. Since an event contains all tenant data, the newest event on the stream always represents the current state of a tenant.

A naive implementation of this system will have several issues: Kafka consumers will automatically commit event offsets every five seconds by default. If the event processor goes down while creating a new tenant, the event still might have been committed although no tenant was created. In effect, the event is considered to be successfully processed when in reality it failed. Much in the same way, the producer can fail to submit an event to Kafka, although the user has already been notified that the operation was successful. So what are the nitty-gritty details required to make our example system transactional?

Infusing transactional properties

In our system, a transaction is represented by a single event only. This means that an event is the most fine-grained unit we read from or write to Kafka. At the same time, events contain all the information necessary for manipulating a tenant. Reading and writing events is therefore inherently atomic, just like transactions in a relational database. That is straightforward, but what about consistency?

In an RDBMS, the database engine is responsible for enforcing constraints and referential integrity. However, Kafka does not know the exact data model. It concerns itself only with binary key-value pairs and cannot enforce any constraints on your data. In order to achieve consistency, the event producer must take care of everything before submitting an event to a Kafka topic. Verifying incoming data is something that needs to be performed anyway, as is the case with our event producer that receives input values via the HTTP API.

When events are sent from one or more producers to Kafka, Kafka will preserve the order of events. This is not a global ordering across partitions but rather a total ordering within each partition. Luckily, Kafka ensures that all of a partition’s events will be read by the same consumer so no event will be processed by two conflicting consumers. Each event is processed in isolation from other events, regardless of the number of partitions and consumers, as long as all processors of a specific event type are in the same consumer group.

Lastly, in order to achieve durability in our system, the event producer and processor must pay special attention to acknowledgements and commits. If a user requests the creation of a new tenant via the API, the producer needs to delay the response to the user until the tenant event is acknowledged by the Kafka cluster. Kafka’s durability guarantees now prevent the event from being lost if the API service goes down. Note that you can tune the level of durability based on the requested type of acknowledgement (ack): producers may request no ack at all, an ack by the leader, or an ack from the cluster as soon as the minimum number of replicas are in sync.

Once the event is persisted, it needs to be consumed by an appropriate event processor, though the processor may go down before it has finished. If auto-commit is enabled for the Kafka consumer, the event processor might already have commited the event offset and fail before finishing the event. The consumer must commit the event manually after all relevant sub-processes have completed. For example, if a new tenant was created and that tenant had to be registered with a third-party payment provider, the consumer delays committing the event until the tenant is successfully registered with the payment service. Only the synergy between the event producer, processor, and Kafka allows for proper durability.

Prerequisites and limitations of the architecture

At this point, our system has most of the benefits that come with ACID transactions in relational databases: a user’s actions are atomic, consistency is handled by event producers, events are isolated by design, and durability is guaranteed by smart acks and commits. But to continue on this path, there are more considerations.

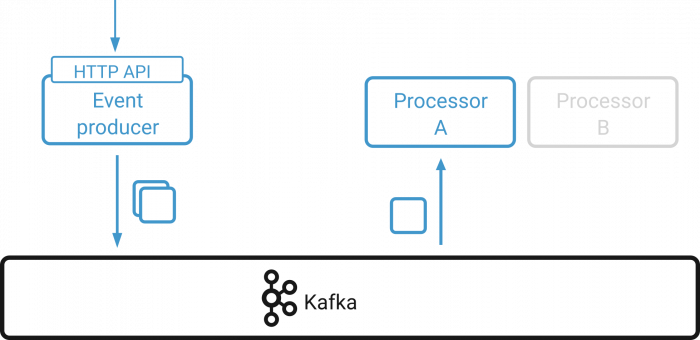

Modeling events and transactions

The system was initially presented as “event based.” Yet, there are different ways to design events, and this term does not enforce any particular style. In our context, events should be self-contained. A tenant event, for example, should encapsulate all information about that tenant so that no dependencies on other events exist. This is referred to as event-carried state transfer. A transaction may in turn consist of one or more events. The following image depicts a producer that sends two events representing a single transaction to a Kafka topic and two event processors in the same consumer group that read events from the topic.

There may be cases where the first part of a transaction is processed by the consumer and a rebalance kicks in. The partition to which both events were sent are now processed by a different consumer that might lack the context of the previous events.

This problem can be tackled in several different ways. One possibility is to require Processor B to reprocess the partition, which would require careful attention to avoid side effects. It is also worth noting that rebalances occur infrequently, whereas events occur frequently. If the partition grows quickly and event processing is slow in comparison, reprocessing the partition may take a long time.

Kafka Streams takes care of the issue in a different way. Each Kafka Streams task contains a state store that is required for functionality involving multiple dependent messages like windowing. The tasks are aware of rebalances and migrate the state accordingly between event processors. Therefore, Processor B knows about the event processed by Processor A.

The most robust way to represent a transaction is to model a transaction as a single event. We previously established that events are atomic. If an event always corresponds to a single transaction, this transaction will also be processed atomically.

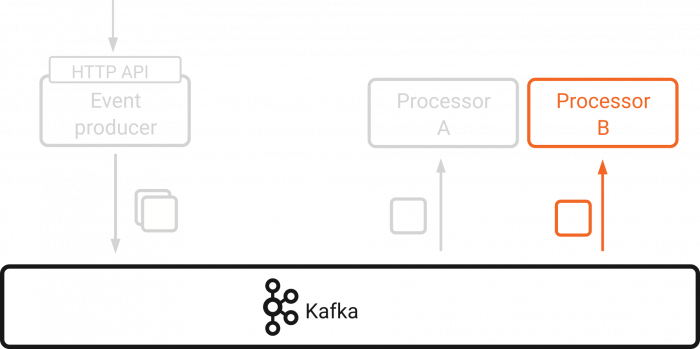

API consistency

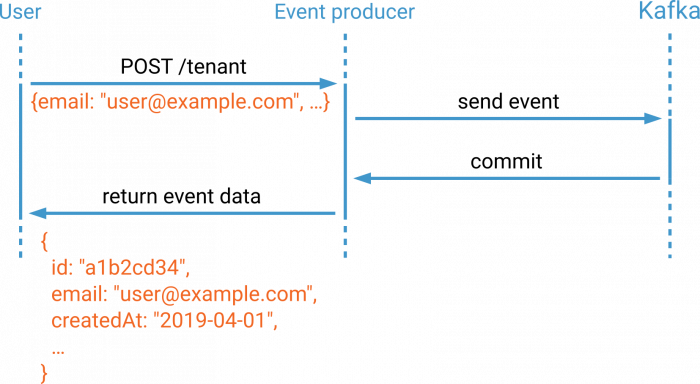

Even though event producers are responsible for maintaining referential integrity and other constraints on the data model, the API itself will only be eventually consistent for clients. The event producers and consumers are asynchronously decoupled through Kafka. If the client creates a new tenant and immediately reads it, chances are that the tenant was not yet created and the request fails. This is a fundamental design decision, but alleviating the issue is possible. There is no need for clients to query the API if it always returns newly created entities in its response. The following image shows a user who creates a new tenant. The event producer awaits the commit and returns the contents of the committed event back to the user.

The returned data may be filtered, of course, in order to prevent internal information from leaking to the user. Paired with a client-side library, this approach can hide the eventually consistent behavior from the client.

Idempotent event processing

Many things can go wrong in a distributed system. Requests to the HTTP API could be received twice due to network issues. Furthermore, since event producers, consumers, and Kafka reside on different hosts, a consumer may crash halfway through processing an event. Consequently, it is important to make sure that duplicate requests or events do not modify our system state twice. We need to make the system idempotent. Although this property is very specific to the individual application, we can take measures in two different areas: communication between the user, and the HTTP API or communication between event producer and the event processor.

Our example client uses HTTP to communicate with the event producer. HTTP verbs, such as PUT or DELETE, are idempotent by definition, but operations like POST require special treatment. One possibility is to add an additional HTTP header to requests by which the HTTP server can identify whether a request was sent twice. This unique ID can also be part of the request data. Anything goes, as long as the client and the server agree.

If we do not want to impose constraints on the client, we still have ways to make the event producers and consumers idempotent. For example, a producer can derive the tenant key from unique properties of the tenant, such as email address. Duplicate POST requests will then lead to two events with the same keys and values. From there, event processors ensure that only a tenant with a specific key is created, if it does not yet exist.

Adding more services

The discussed system is just a toy example, but the architecture can be extended to more than a single entity, following the principles of domain-driven design or self-contained systems. Adding producers and consumers for each entity results in a number of “verticals” that are highly decoupled through Kafka.

![Tenant App | User App [...] Job Processing App](https://cdn.confluent.io/wp-content/uploads/Services-1-e1566232280210.png)

The event producers and processors need not be separate deployment units. In fact, they might just be two asynchronous subroutines within an application. Even a monolithic deployment works.

The example system assumes that duplicate messages will occur and is designed to handle them gracefully. If you cannot have duplicates, you might want to look into Kafka transactions, which provide exactly once delivery semantics. Together with Kafka Streams, they can be used as a building block for connecting a landscape of services with exactly once semantics.

Final thoughts

The presented example system supports atomic, isolated, and durable operations for creating, modifying, and deleting single tenants, in which event producers handle consistency. The system can be scaled horizontally by adding additional partitions to the tenant topic as long as all tenant events are written to the same topic.

There are other approaches to modeling transactions in a stream processing application. This includes promoting events through a chain of topics based on event state. Following this approach, our tenant events might be submitted to the topic tenant-pending. There, they are picked up by an event processor that sets up the integration for the third-party payment provider and submits events to either the tenant-created or the tenant-failed topic.

There are many different ways to build systems around Apache Kafka and this article presented just one. If you would like, you can download the Confluent Platform to get started with the leading distribution of Apache Kafka.

My thanks go to Thomas Bayer who provided the initial architectural sketch, to the reviewers, Stefan Seifert and Ben Stopford, and to Victoria Yu for copyediting.

Did you like this blog post? Share it now

Subscribe to the Confluent blog

Introducing KIP-848: The Next Generation of the Consumer Rebalance Protocol

Big news! KIP-848, the next-gen Consumer Rebalance Protocol, is now available in Confluent Cloud! This is a major upgrade for your Kafka clusters, offering faster rebalances and improved stability. Our new blog post dives deep into how KIP-848 functions, making it easy to understand the benefits.

How to Query Apache Kafka® Topics With Natural Language

The users who need access to data stored in Apache Kafka® topics aren’t always experts in technologies like Apache Flink® SQL. This blog shows how users can use natural language processing to have their plain-language questions translated into Flink queries with Confluent Cloud.