Kafka in the Cloud: Why it’s 10x better with Confluent | Find out more

Introducing Kafka Streams: Stream Processing Made Simple

I’m really excited to announce a major new feature in Apache Kafka v0.10: Kafka’s Streams API. The Streams API, available as a Java library that is part of the official Kafka project, is the easiest way to write mission-critical, real-time applications and microservices with all the benefits of Kafka’s server-side cluster technology.

A stream processing application built with Kafka Streams looks like this:

Despite being a humble library, Kafka Streams directly addresses a lot of the hard problems in stream processing:

- Event-at-a-time processing (not microbatch) with millisecond latency

- Stateful processing including distributed joins and aggregations

- A convenient DSL

- Windowing with out-of-order data using a DataFlow-like model

- Distributed processing and fault-tolerance with fast failover

- Reprocessing capabilities so you can recalculate output when your code changes

- No-downtime rolling deployments

For those who want to skip the preamble and just dive into the docs, you can just go to the Kafka Streams documentation. The purpose of this blog post will be less the “what”, which the documentation covers in depth, and more the “why”.

But wait, what exactly is it?

Kafka Streams is a library for building streaming applications, specifically applications that transform input Kafka topics into output Kafka topics (or calls to external services, or updates to databases, or whatever). It lets you do this with concise code in a way that is distributed and fault-tolerant. Stream processing is a computer programming paradigm, equivalent to data-flow programming, event stream processing, and reactive programming, that allows some applications to more easily exploit a limited form of parallel processing.

There is a wealth of interesting work happening in the stream processing area—ranging from open source frameworks like Apache Spark, Apache Storm, Apache Flink, and Apache Samza, to proprietary services such as Google’s DataFlow and AWS Lambda—so it is worth outlining how Kafka Streams is similar and different from these things.

Frankly there is a ton of the kind of messy innovation that open source is so good at happening right now in this ecosystem. We’re pretty excited about all these different processing layers: even though it can be a bit confusing at times, the state of the art is advancing pretty quickly. We’re working hard to make Kafka work really well as a data source with all of these. The gap we see Kafka Streams filling is less the analytics-focused domain these frameworks focus on and more building core applications and microservices that process real time data streams. I’ll dive into this distinction in the next section and start to dive into how Kafka Streams simplifies this type of application.

Hipsters, Stream Processing, and Kafka

The only way to really know if a system design works in the real world is to build it, deploy it for real applications, and see where it falls short. In a previous role, at LinkedIn, I was lucky enough to be part of the team that conceived of and built the stream processing framework Apache Samza. We rolled it out for a set of in-house applications, supported it in production, and helped open source it as an Apache project.

So what did we learn? Lots. One of the key misconceptions we had was that stream processing would be used in a way sort of like a real-time MapReduce layer. What we eventually came to realize, though, was that the most compelling applications for stream processing are actually pretty different from what you would typically do with a Hive or Spark job—they are closer to being a kind of asynchronous microservice rather than being a faster version of a batch analytics job.

What do I mean by this? What I mean is that these stream processing apps were most often software that implemented core functions in the business rather than computing analytics about the business.

Building stream processing applications of this type requires addressing needs that are very different from the analytical or ETL domain of the typical MapReduce or Spark job. They need to go through the same processes that normal applications go through in terms of configuration, deployment, monitoring, etc. In short, they are more like microservices (overloaded word, I know) than MapReduce jobs. It’s just that this type of data streaming app processes asynchronous event streams from Kafka instead of HTTP requests.

When we looked at how people were building stream processing applications with Kafka, there were two options:

- Just build an application that uses the Kafka producer and consumer APIs directly

- Adopt a full-fledged stream processing framework

Using the Kafka APIs directly works well for simple things. It doesn’t pull in any heavy dependencies to your app. We called this “hipster stream processing” since it is a kind of low-tech solution that appealed to people who liked to roll their own. This works well for simple one-message-at-a-time processing, but the problem comes when you want to do something more involved, say compute aggregations or join streams of data. In this case inventing a solution on top of the Kafka consumer APIs is fairly involved.

Pulling in a full-fledged stream processing framework gives you easy access to these more advanced operations. But the cost for a simple application is an explosion of complexity. This makes everything difficult, from debugging to performance optimization to monitoring to deployment. This is even worse if your app has both synchronous and asynchronous pieces as then you end up splitting your code between the stream processing architecture / framework and whatever mechanism you have for implementing services or apps. It’s just really hard to build and operationalize a critical part of your business in this way.

This isn’t such a problem in all domains—after all, if you are already using Spark to build a batch workflow, and you want to add a Spark Streaming job into this mix for some real time big data analytics, the additional complexity is pretty low and it reuses the skills you already have.

However if you are deploying a Spark cluster for the sole purpose of this new application, that is definitely a big complexity hit.

Since we had designed the core abstractions in Kafka to be the primitives for stream processing we wanted to be able to give something that provides you what you would get out of a stream processing framework, but which has very little additional operational complexity beyond the normal Kafka producer and consumer APIs.

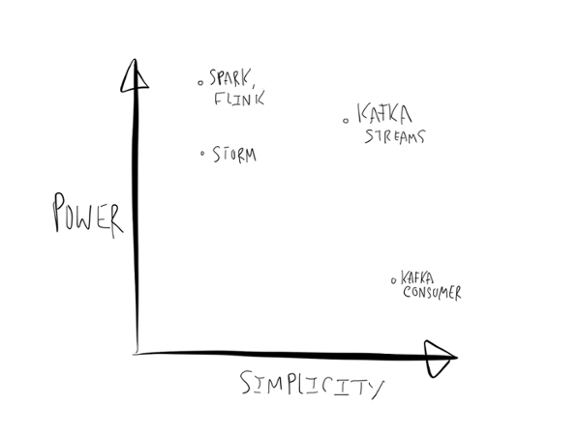

In other words we were aiming for something like this:

Like most graphs of this kind, this is summarizing an argument rather than presenting evidence (don’t ask me what the units for the axes are), but nonetheless I think this reduction in complexity is totally real.

The goal is to simplify stream processing enough to make it accessible as a mainstream application programming model for asynchronous services. This plays out in a bunch of ways, but there are three big areas I think are worth exploring in a little detail in this post:

- Making Kafka Streams a fully embedded library with no stream processing cluster—just Kafka and your application.

- Fully integrating the idea of tables of state with streams of events and making both of these available in a single conceptual framework.

- Giving a processing model that is fully integrated with the core abstractions Kafka provides to reduce the total number of moving pieces in a stream architecture.

Let’s dive into each of those areas.

Simplification 1: Framework-Free Stream Processing

The first aspect of how Kafka Streams makes building streaming services simpler is that it is cluster and framework free—it is just a library (and a pretty small one at that). Kafka Streams is one of the best Apache Storm alternatives. You don’t need to set up any kind of special Kafka Streams cluster and there is no cluster manager, nimbus, daemon processes, or anything like that. If you have Kafka there is nothing else you need other than your own application code. Your app code will coordinate with Kafka to handle failures, divvy up the processing load amongst instances, and rebalance load dynamically if more instances start up.

I’ll walk through why I think this is important and give a little bit of the journey we went through in understanding the importance of this model.

Curing The MapReduce Hangover

I covered already our experience building Samza and the conceptual shear between what we built (real-time MapReduce) and what a lot of people actually wanted (simple streaming services). I think this misconception of the problem is pretty common—after all much of what stream processing is doing is taking capabilities from the batch world and making them available for a low-latency domain. This same MapReduce heritage affects the other major stream processing platforms as much as it does Samza (e.g. Storm, Spark, etc).

At LinkedIn this showed up in a host of production data processing services that sat in a low latency domain: prioritizing emails, standardizing user-generated content, processing newsfeed updates, and so on.

This type of asynchronous service is hardly unique to web companies—logistics companies need to manage and route deliveries in real-time, retailers need to re-order and re-price products that sell out, and real-time data is, in many ways, at the heart of what finance companies are about. Much of business, is, after all, asynchronous, it doesn’t happen in the course of rendering a web page or updating a mobile app screen.

Why is building this type of core app on top of stream processing frameworks like Storm, Samza, and Spark Streaming so tricky?

A batch processing framework like MapReduce or Spark needs to solve a bunch of hard problems:

- It has to multiplex a large number of transient jobs over a pool of machines, and efficiently schedule resource distribution in the cluster.

- To do this it has to dynamically package up your code and physically deploy it to the machines that will execute it, along with configuration, libraries, and whatever else you need to run

- It has to manage processes and try to guarantee isolation between “jobs” sharing the cluster.

Unfortunately tackling these problems makes the frameworks pretty invasive. In exchange for fault-tolerance and scalability, they want to control many aspects of how code is deployed, configured, monitored, and packaged.

More modern processing frameworks have done a good job of attempting to paper over this, but you can’t escape the fact that the framework is attempting to somehow serialize your code, and send it over the network. Often this is done in a way that would give you pause if you thought about this as what it is—a deployment mechanism.

So What Does Kafka Streams Do Instead?

Kafka Streams is much more focused in the problems it solves. It does the following:

- Balance the processing load as new instances of your app are added or existing ones crash

- Maintain local state for tables

- Recover from failures

This is accomplished by using the exact same group management protocol that Kafka provides for normal consumers. The result is that a Kafka Streams app is just like any other service. It may have some local state on disk, but that is just a cache that can be recreated if it is lost or if that instance of the app is moved elsewhere. You just use the library in your app, and start as many instances of the app as you like, and Kafka will partition up and balance the work over these instances.

This is particularly important for doing simple things like rolling restarts or no-downtime expansion—things which we take for granted in modern software engineering but which are still out of reach in many stream processing frameworks.

Docker, Mesos, and Kubernetes, Oh My!

One of the reasons that separating out packaging and deployment from the stream processing framework is so important is because packaging and deployment is an area undergoing its own renaissance. Kafka Streams apps can be deployed using classic ops tools like Puppet, Chef, Salt, or just by starting the processes from the command line. You can package your app as a Docker image if you’re young and hip, or as a WAR file if you’re not.

One of the reasons that separating out packaging and deployment from the stream processing framework is so important is because packaging and deployment is an area undergoing its own renaissance. Kafka Streams apps can be deployed using classic ops tools like Puppet, Chef, Salt, or just by starting the processes from the command line. You can package your app as a Docker image if you’re young and hip, or as a WAR file if you’re not.

But for those looking for more elastic management, there are a host of frameworks that aim to make applications more dynamic. A partial list would include:

- Apache Mesos with a framework like Marathon

- Kubernetes

- YARN with something like Slider

- Swarm from Docker

- Various hosted container services such as ECS from Amazon

- Cloud Foundry

This ecosystem is almost as confusing as the stream processing ecosystem!

Indeed the problem Mesos and Kubernetes are trying to solve is the placement of processes on machines, and this is the same as the problem a Storm cluster is trying to solve when you deploy a Storm job into a Storm cluster. The critical difference is that this problem turns out to be hard and these general purpose frameworks, at least the better ones, are vastly better at it—they let you do things like rolling restarts with controlled parallelism, sticky host affinity, real cgroups-based isolation, packaging with docker, slick UIs, etc.

You can use Kafka Streams in any of these frameworks, just as you would any other application and this is an easy way to get dynamic elasticity in managing processes. For example, if you have Mesos and Marathon, you can just directly launch your Kafka Streams application via the Marathon UI and scale it dynamically without downtime—Mesos takes care of managing processes and Kafka takes care of balancing load and maintaining your job’s processing state.

The overhead of adopting one of these frameworks is comparable to operationalizing the cluster management pieces of something like Storm, but the advantage is that these frameworks are totally optional (and of course Kafka Streams works totally fine without them).

Simplification 2: Streams Meet Tables

The next key way Kafka Streams simplifies streaming applications is that it fully integrates the concepts of tables and streams. We’ve talked about this idea before as a way of “turning the database inside out”. That phrase captures the flavor of how the resulting system recasts the relationship between an application and its data, as well as in how it reacts to data changes. To understand this I’ll back up and explain what I mean by “table” and “stream” and why combining these things simplifies a whole host of common patterns for asynchronous apps.

Traditional databases, of course, are all about storing tables full of state. What databases don’t do a great job of is reacting to streams of events. What’s an event? An event is just something that has happened in the world—it could be a click, a sale, a location ping from a sensor, or virtually any other occurrence in the world.

Stream processing systems like Storm have started from the other side of the equation. They are built to process a stream of events, but the idea of state computed off this stream is something of an afterthought.

I’ll argue that the fundamental problem of an asynchronous application is combining tables that represent the current state of the world with streams of events about what is happening right now. Frameworks need to do a good job of representing both these things and translating them back and forth.

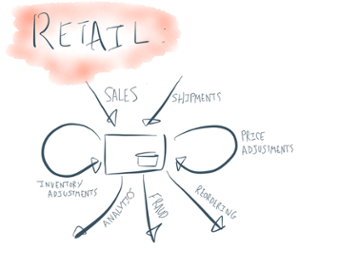

How do these concepts relate? Consider a simple model of a retail store. The core streams in retail are sales of products, orders placed for new products, and shipments of products that arrive. The “inventory on hand” is a table computed off the sale and shipment streams which add and subtract from our stock of products on hand. Two key stream processing  operations for a retail outlet are re-ordering products when the stock starts to run low, and adjusting prices as supply and demand change. A real worldwide retailer is, of course, vastly more complicated since logistical shipments are managed across a worldwide network of warehouses and stores, and a host of analytics and inventory adjustments, but understanding how to model real-world things as a combination of tables and streams is key.

operations for a retail outlet are re-ordering products when the stock starts to run low, and adjusting prices as supply and demand change. A real worldwide retailer is, of course, vastly more complicated since logistical shipments are managed across a worldwide network of warehouses and stores, and a host of analytics and inventory adjustments, but understanding how to model real-world things as a combination of tables and streams is key.

Tables and Streams are Dual

Before we get into stream processing, let’s just start by trying to understand the relationship between tables and streams. I think it’s best summed up by this quote about databases and logs from Pat Helland:

“Transaction logs record all the changes made to the database. High-speed appends are the only way to change the log. From this perspective, the contents of the database hold a caching of the latest record values in the logs. The truth is the log. The database is a cache of a subset of the log. That cached subset happens to be the latest value of each record and index value from the log.”

What on earth does this mean? The meaning is actually at the heart of the relationship between tables and streams.

Let’s start by asking this question: What is a stream? Well that is easy, a stream is a sequence of records. Kafka models a stream as a log, that is, a never-ending sequence of key/value pairs:

key1 => value1key2 => value2key1 => value3...

What is a table? I think we all know, a table is something like this:

| key1 | value3 |

| key2 | value2 |

The value could be complex in which case it would be split into multiple columns, but we can ignore that detail for now and just think of key-value pairs (adding more columns won’t change anything material for this discussion).

But whereas our stream continued to evolve over time with new records appearing, this is just a snapshot of our table at a point in time. How do tables evolve? They get updated. A table isn’t really a single thing, but more a series of things like

time = 0

| key1 | value1 |

time = 1

| key1 | value1 |

| key2 | value2 |

time = 2

| key1 | value3 |

| key2 | value2 |

But this sequence has a bunch of redundancy. If we factor out the rows that didn’t change and just record the updates then another way to visualize the table would be as an ordered sequence of updates:

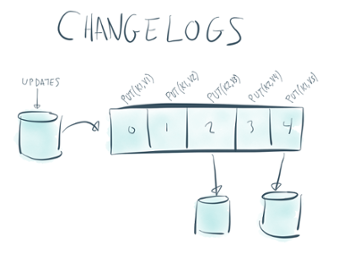

put(key1, value1)put(key2, value2)put(key1, value3)...

Or, if we get rid of the put since that is implied, then we have

key1 => value1key2 => value2key1 => value3...

But that is just a stream! This particular form of streamed data is often called a changelog as it denotes the sequence of updates, recording the latest value of each record in the order of update.

So tables are just a particular view on a stream. It may seem odd to think this way, but I’d argue that this form of a table is actually just as essential to what a table truly is as the rectangular table thing we all picture in our minds. Perhaps it is actually more natural since it captures the concept of evolution over time (and think about it: what data do you really have that doesn’t change?).

In other words, as Pat Helland pointed out, a table is just a cache of the latest value for each key in a stream.

Another way to put this is in database terms: a pure stream is one where the changes are interpreted as just INSERT statements (since no record replaces any existing record), whereas a table is a stream where the changes are interpreted as UPDATEs (since any existing row with the same key is overwritten).

This duality has been built into Kafka for some time and shows up as compacted topics.

Tables and Stream Processing

Okay, so that is what tables and streams are, now why does this matter for stream processing? Well, it turns out that the relationship between streams and tables is at the core of what stream processing is about.

I gave the retail example already where a stream of product shipments and sales result in a table of inventory “on hand”, and changes to the inventory that is on hand in turn trigger processes like reordering and price changes.

In this example the tables obviously aren’t just things created in a stream processing framework, though, they are probably out there in databases already. That’s fine, capturing a stream of changes to a table is called Change Capture, it’s a thing databases do. The format of change capture data stream is exactly the changelog format I described. This kind of change capture is something you can do fairly easy using Kafka Connect, a framework that is built for data capture and was newly added to Apache Kafka in the 0.9 release.

By modeling the table concept in this way, Kafka Streams lets you compute derived values against the table using just the stream of changes. In other words it lets you process database change streams just as you would a stream of clicks.

You can think of this functionality of triggering computation based on database changes as being analogous to the trigger and materialized view functionality built into databases but instead of being limited to a single database and implemented only in PL/SQL, it operates at datacenter scale and can work with any data source.

Joins and Aggregates are Tables Too

So we’ve explored how we can take a table, turn it into a stream of updates (a changelog) in Kafka, and compute derived things off this using Kafka Streams. But the table/stream duality works in reverse too.

Let’s say I have a stream of user clicks coming in and I want to compute the total number of clicks for each user. Kafka Streams lets you compute this aggregation, and the set of counts that are computed, is, unsurprisingly, a table of the current number of clicks per user.

In terms of implementation Kafka Streams stores this derived aggregation in a local embedded key-value store (RocksDB by default, but you can plug in anything). The output of the job is exactly the changelog of updates to this table. This changelog is used for high-availability of the computation, but it’s also an output that can be consumed and transformed by other Kafka Streams processing or loaded into another system using Kafka Connect.

Architecturally this idea of supporting local storage was already present in Apache Samza and I wrote about it before primarily from a systems real time analytics architecture point of view. The key new thing in Kafka Streams is that the table concept isn’t just a low-level facility, it’s a first class citizen just as streams themselves are. Streams are represented by the KStream class in the programming DSL provided by Kafka Streams, and tables by the KTable class. They share a lot of the same operations, and can be converted back and forth just as the table/stream duality suggests, but, for example, an aggregation on a KTable will automatically handle that fact that it is made up of updates to the underlying values. This matters, as the semantics of computing a sum over a tables undergoing updates and a stream of immutable updates are totally different; likewise the semantics of joining two streams (say clicks and impressions) are totally different from the semantics of joining a stream to a table (say clicks to user accounts). By modeling these two concepts in the DSL, these details fall out automatically.

Windows and Tables

Windowing, time, and out-of-order events are another tricky aspect of stream processing. And it turns out, somewhat surprisingly, that a very simple solution falls naturally out of the very same table concept. Those who closely follow the stream processing area may have heard of the idea of “event time” that has been really eloquently discussed by the folks on the Google Dataflow team. The question they grappled with was how to do windowed operations on streams if events can arrive out of order. This problem of out-of-order data is quite unavoidable in most distributed settings since we simply can’t guarantee order over data being generated in different data centers or on different devices.

An example of this type of windowed computing in the retail domain would be computing the number of sales per product over a ten minute window. How can you know when the window is complete, and that all the sales with a timestamp in that range have arrived and been processed? And if you can’t know this how can you give a final answer for the count? Whenever you choose to answer with your count it may be too early and more events may arrive late causing your original output to be wrong.

Kafka Streams makes handling this really simple: the semantics of a windowed aggregation like a count is that it represents the count “so far” for the window. It is continuously updated as new data arrives and allows the downstream receiver to decide when it is complete. And yes, this notion of an updatable quantity should seem eerily familiar: it is nothing more than a table where the window being updated is part of the key. Naturally downstream operations know that this stream represents a table, and process these refinements as they come.

I think it is kind of elegant that the same mechanism that allows computing things on top of database change capture streams allows for handling windowed aggregates with out-of-order data. This relationship between tables and streams isn’t something we invented, it’s been explored in a lot of detail by older stream processing literature such as CQL, but it isn’t captured in most real-world systems—databases handle tables, and stream processing systems handle streams, and not much handles both as first class citizens.

Tables + Embeddable Library = Stateful Services

There is an emergent property of some of the features I just described that may not be obvious. I discussed how Kafka Streams lets you transparently maintain derived tables in RocksDB or other local data structures. Because this processing and the state it creates physically resides in your application, this opens up another avenue of usage which is really fascinating: allowing the application to directly query this derived state.

We haven’t exposed the hooks to do this yet—we’re focusing on stabilizing the stream processing APIs first—but I think this is a very promising architecture for certain types of data-intensive applications.

This means you can build, say, a REST service that embeds Kafka Streams and directly queries the local aggregates being computed by the stream processing operators off of incoming data streams. The advantages of this kind of stateful service are discussed here. This doesn’t make sense in all domains—often you just want to produce your output to an external database you know and trust. But in cases where your service needs to access a lot of data per request, having this data in the local memory or in a fast local RocksDB instance can be quite powerful.

Simplification 3: Simple Is Beautiful

Our overriding objective in all of this is to make the process of building and operating a stream processing application far simpler. Our belief is that stream processing should be a mainstream way of building applications, and a huge portion of what companies do is naturally in the asynchronous domain that stream processing is built for. But to make this practical we need to make it easy enough to depend on in this way. Part of this operational simplicity comes from getting rid of the need for an external cluster, but there is more to it than that.

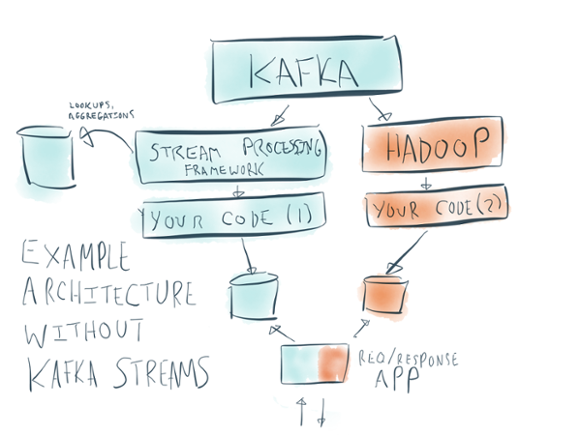

If you look at how people tend to build stream processing applications, beyond the framework itself, they tend to be intensely architecturally complex. Here is an example architecture diagram for a typical stream processing application:

There are sooo many moving parts here:

- Kafka itself

- A stream processing cluster for Storm or Spark or whatever, which is usually a set of master processes and per-node daemons

- Your actual stream processing job

- A side-database for lookups and aggregations

- A database for outputs that will be queries by the app and which takes the output of the stream processing job

- A Hadoop cluster (which is itself a dozen odd moving parts) for reprocessing data

- The request/response app that serves live requests to your users or customers

Plunking down a monstrosity like this is not only undesirable, it’s often not even feasible. Even if you have all these pieces already, tieing them all together into a well-monitored, fully operationalized whole is fiercely difficult.

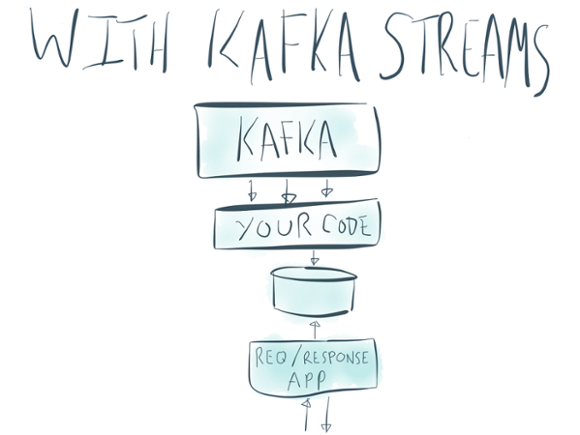

One of the most pleasant things about Kafka Streams is that the core concepts are few and they’re carried throughout the system.

We’ve talked about a couple of the big ones: getting rid of the additional stream processing cluster and making tables and stateful processing fully integrated into the stream processor itself. With Kafka Streams this architecture can be shrunk to something like this:

But this idea of making streaming simple goes well beyond these two things.

Since it builds directly on Kafka’s primitives, Kafka Streams is actually quite small. The full code base is less than 9k lines of code. You can read it in an afternoon if you like. This means the additional complexity you incur beyond Kafka’s own producer and consumer client is quite bearable.

This plays out in dozens of small ways:

- The inputs and outputs are just Kafka topics

- The data model is just Kafka’s keyed record data model throughout

- The partitioning model is just Kafka’s partitioning model, a Kafka partitioner works for streams too

- The group membership mechanism that manages partitions, assignment, and liveness is just Kafka’s group membership mechanism

- Tables and other stateful computations are just log compacted topics.

- Metrics are unified across the producer, consumer, and streams app so there is only one type of metric to capture for monitoring

- The position of your app is maintained by the application’s offsets, just as any Kafka consumer

- The timestamp used for windowing is the timestamp being added to Kafka itself in the 0.10 release, providing you with event-time processing

In short a Kafka Streams application looks in many ways just like any other Kafka producer or consumer but it is written vastly more concisely.

The number of configuration parameters beyond the basics exposed by the Kafka clients is quite minimal.

If you change your code and need to reprocess data with the new logic this doesn’t necessitate a whole different system, you can just rewind the Kafka offsets of your application and have it reprocess its input. (You can, of course, also do the reprocessing in Hadoop or elsewhere if you want, but the key thing is that you don’t have to).

Whereas the original example architecture was a set of independent pieces that only partially work together, we hope that you will feel that Kafka, Kafka Connect, and Kafka Streams all feel like things built to work together.

What’s Next

As with any early release there are a couple of things that are coming up that we haven’t done yet. Here’s a few things that will be coming up next.

Queryable State

As mentioned earlier, one of the advantages of an embeddable library combined with the capability of storing partitioned random access tables is the ability to go beyond the use of the tables for look-ups by the application embedding the processing. We’ll be adding this feature in the coming releases.

End-to-End Semantics

The current version of Kafka Streams inherits Kafka’s semantics which are often described as “at least once delivery”. The broader Kafka community has done a lot of thought and exploration into how to strengthen these guarantees in a way that would provide an end-to-end story across Kafka Connect, Kafka itself, and Kafka Streams or other computation engines along with their derived tables or state. We’ll be diving into this area in the upcoming months and get some proposals out for discussion.

Supporting languages beyond Java

One of the nice things about this approach is that the amount of code is quite small and we think it should be possible to build out a really nice implementation in a number of major languages and still have them feel like natives of their ecosystem. We’re focusing on getting the normal clients in shape there first, but we’ll pick up working on stream processing support shortly after.

Try It Out

If you have enjoyed this article, you might want to continue with the following resources to learn more about stream processing on Apache Kafka:

- Get started with the Kafka Streams API to build your own real-time applications and microservices

- Walk through our Confluent tutorial for the Kafka Streams API with Docker and play with our Confluent demo applications

- Check out fully managed Apache Kafka as a service with Confluent Cloud and receive $400 of free usage during your first 60 days, plus an additional $60 of free usage when you use the promo code CL60BLOG*

We’d love to hear about anything you think is missing or ways it can be improved: chime in on the Apache Kafka mailing list with any thoughts, feedback, bugs—we’d love to work really closely with early people kicking the tires so don’t be shy.

Also, if you’re interested in this stuff and want to help build it, Confluent is hiring. 🙂

Did you like this blog post? Share it now

Subscribe to the Confluent blog

Introducing Versioned State Store in Kafka Streams

Versioned key-value state stores, introduced to Kafka Streams in 3.5, enhance stateful processing capabilities by allowing users to store multiple record versions per key, rather than only the single latest version per key as is the case for existing key-value stores today...

Delivery Guarantees and the Ethics of Teleportation

This blog post discusses the two generals problems, how it impacts message delivery guarantees, and how those guarantees would affect a futuristic technology such as teleportation.