OSS Kafka couldn’t save them. See how data streaming came to the rescue! | Watch now

The Rise of Managed Services for Apache Kafka

As a distributed system for collecting, storing, and processing data at scale, Apache Kafka® comes with its own deployment complexities. Luckily for on-premises scenarios, a myriad of deployment options are available, such as the Confluent Platform which can be deployed on bare metal, virtual machines, containers, etc. But deployment is just the tip of the iceberg.

When it comes to Apache Kafka in the cloud, a number of considerations come into play: picking which compute instance is appropriate for the brokers, sizing the non-ephemeral storage accordingly, applying end-to-end security measures, ensuring high availability through availability zones, figuring out effective recoverability strategies to ensure SLAs, applying continuous observability practices, upholding data regulations, onboarding developers, etc. To simplify all of this, different providers have emerged to offer Apache Kafka as a managed service.

Although the concept of managed services is fairly common in databases (e.g., BigQuery, Amazon Redshift, and MongoDB Atlas) and caches (e.g., Cloud Memorystore, Amazon ElastiCache, and Azure Cache), applying this concept to a distributed streaming platform is fairly new. Before Confluent Cloud was announced, a managed service for Apache Kafka did not exist. This has changed over time, and we’d like to share some tips on how you can go about choosing the best option. This blog post goes over:

- The complexities that users will run into when self-managing Apache Kafka on the cloud and how users can benefit from building event streaming applications with a fully managed service for Apache Kafka

- How to differentiate a managed service from a purely hosted solution and also differentiate between a fully managed service and a partially managed service

- Key characteristics of a fully managed service that you can trust for production and mission-critical applications

How do you spot a true fully managed service for Apache Kafka?

In order to answer this question, let’s start by understanding what Apache Kafka in fact is. Contrary to popular belief, it is not just another messaging technology but rather a distributed streaming platform.

Figure 1. Description from the Apache Software Foundation about what Kafka is

A distributed streaming platform combines reliable and scalable messaging, storage, and processing capabilities into a single, unified platform that unlocks use cases other technologies individually can’t. For example, traditional databases offer storage and data retrieval capabilities of past data, but they don’t help much if we need to asynchronously process future events, which is commonly in the arena of messaging technologies. In the same way, messaging technologies don’t have storage, thus they cannot handle past data.

By combining messaging and storage, Apache Kafka is able to handle both future and past data using the same underlying storage known as distributed commit log. This significantly reduces the number of network roundtrips often required to process both when they are being handled by different technologies. With stream processing capabilities that allow you to handle events as they happen (i.e., present data that is still in transit), Apache Kafka is the only technology capable of handling data from every point in time—past, present, and future—opening up the door for event streaming applications.

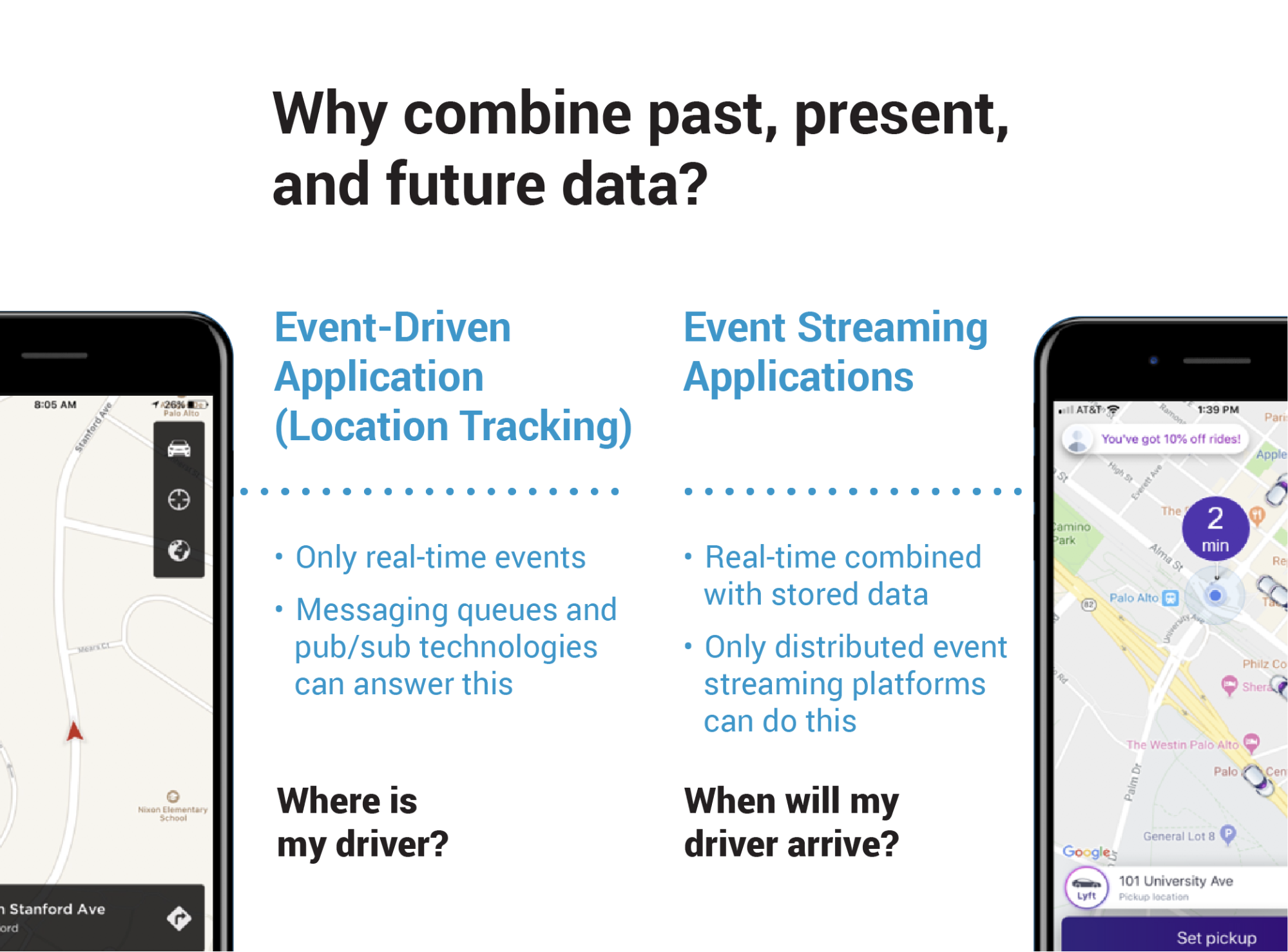

Figure 2. Event streaming applications are more common than you think.

Event streaming applications are changing the way people interact with services, hence the explosion of Kafka usage in recent years. To fully harness the power of Apache Kafka, developers should not rely only on messaging but leverage storage and stream processing capabilities as well. However, doing so can be a huge lift.

Managed service vs. hosted solution

Fortunately, there are managed services that provide the experience of using Apache Kafka without requiring knowledge on how to operate it. This is a characteristic of true managed services, because they must keep developers focused on what really matters, which is coding.

Hosted solutions are different. Some products may automatically create Kafka clusters in a dedicated compute instance and provide a way to connect to it, but eventually, users might need to scale the cluster, patch it, upgrade it, create backups, etc. In this case, it is not a managed solution but instead a hosted solution. The key distinction is that the user still has the responsibility of managing Apache Kafka as if it were running on-premises. Using hosted solutions to develop event streaming applications is just as hard as self-managing Kafka.

Most hosted solutions ask the user to provide a VPC. A VPC is an isolated network that allows resources to be launched. This is a cloud building block that belongs to the IaaS (infrastructure as a service) domain and involves many important design decisions. To provide a VPC, it must be created first, and therefore the user is manually making design decisions. Moreover, to create a VPC, the user must own the compute and network resources (another aspect of a hosted solution) and ultimately prove that the service doesn’t follow serverless computing model principles.

Hosted solutions may also ask users to specify how much storage per broker will be required. This delegates the responsibility of sizing to the user, which is an extremely complicated task that often leads to over-provisioning as a way to compensate for the lack of precision. Over-provisioning means that users will pay for resources that are not being used.

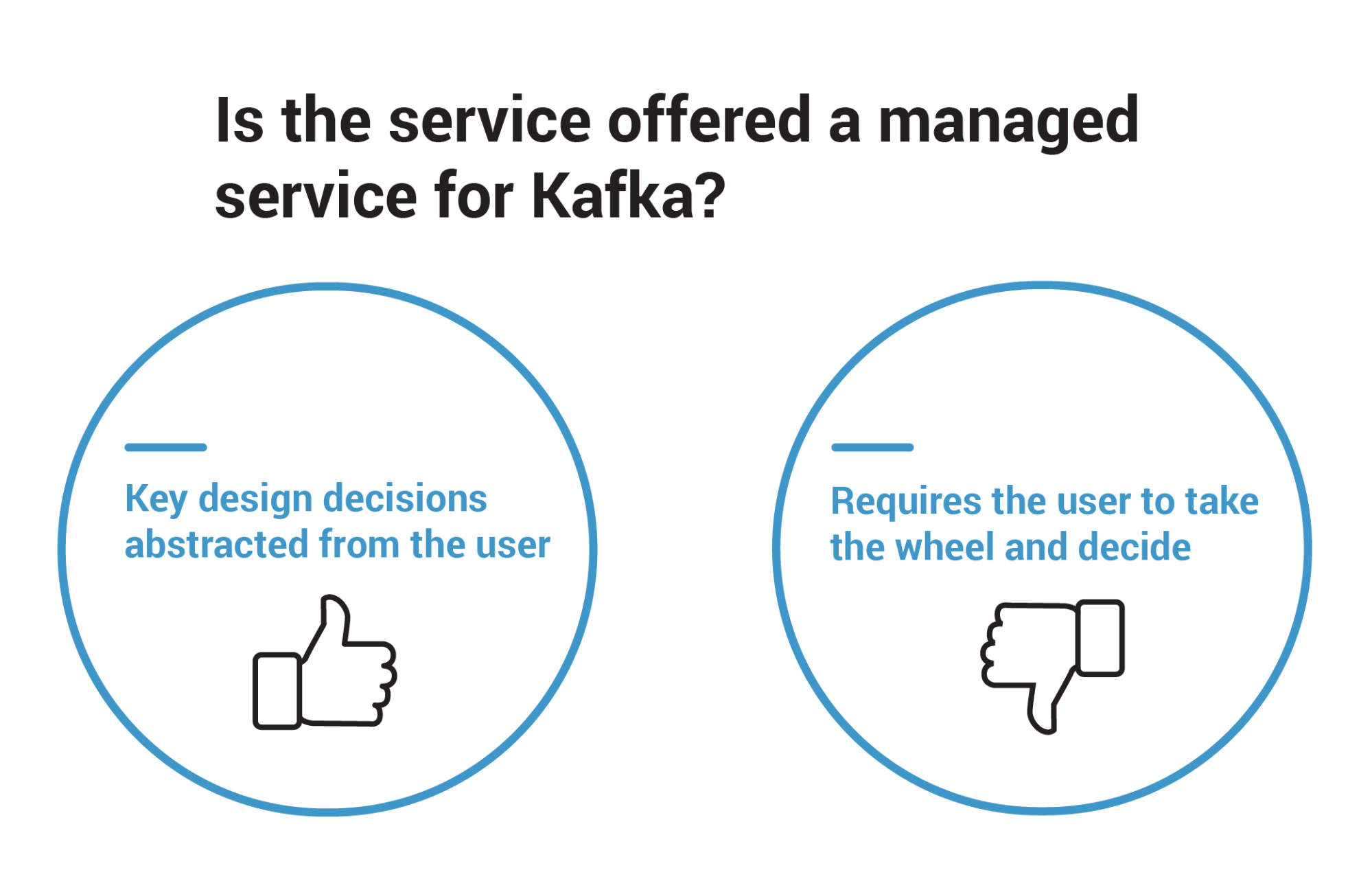

Figure 3. Managed services should not request the user to make hard design decisions.

A managed service should never put the user’s hand on the wheel to make hard decisions, such as:

- Deciding details about how much hardware (e.g., CPU, memory, and disk) to use

- Exposing details about the underlying network and compute infrastructure

- Asking about the number of servers for a given component (aka sizing)

- Asking the user to update the Kafka bits when a new release is made available

- Installing the bits to enable stream processing separately

If a company needs to have control over all technical decisions around their Kafka deployment, note that it doesn’t necessarily need a managed service. It can simply use the Confluent Platform, which offers a complete set of tools for production deployments, as well as Confluent Operator to deploy Confluent Platform on Kubernetes. You can read more about Confluent Operator in this blog post from Neha Narkhede, CPO of Confluent, where she explains the motivations behind the technology and what problems it solves.

Fully managed services vs. partially managed services

Another aspect to consider while evaluating managed services is simplicity. By simplicity, we mean that the experience of using Kafka is as fast and as painless as possible. This can be measured in various ways, but for the sake of this blog post, we will stick with two simple measures:

- How many steps until you start working with Apache Kafka

- How long each step takes to complete

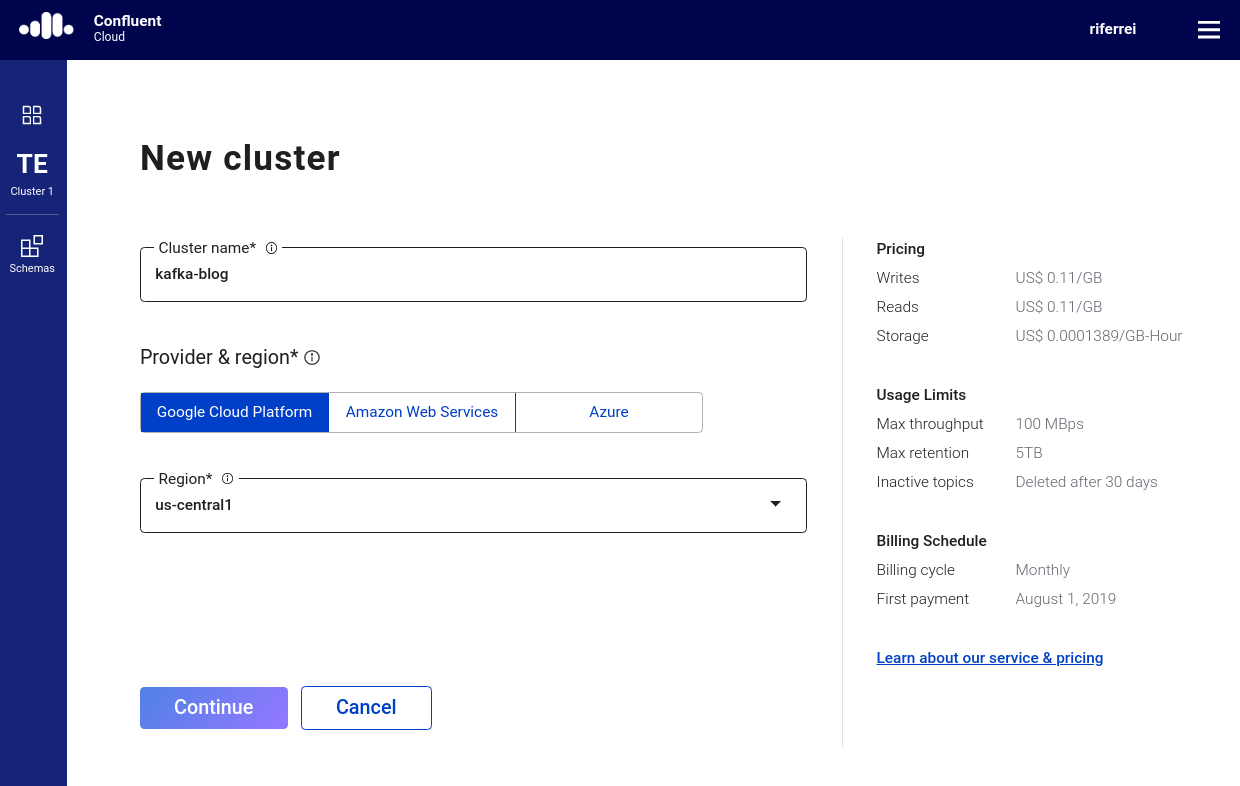

Confluent Cloud for instance, allows the user to effectively start working with Apache Kafka in 90 seconds. Now from the application perspective, all the information required to start working with Apache Kafka is in the bootstrap servers endpoint, which is the cluster that your application will connect to, and the API key and secret used to identify your application. On GitHub, you can find an example of a Go program that connects to a cluster in Confluent Cloud, creates a topic, writes a single record, and creates a consumer to read records from the topic.

If a managed service involves many complicated steps before the application is able to connect to Kafka, it is a partially managed service. Partially managed services introduce co-responsibility between the user and the provider. In this context, the provider asks the user to perform certain tasks to offload its own responsibility, and oftentimes these tasks are the hard ones.

Figure 4. Criteria that separates fully managed services from partially managed services

For instance, partially managed services may ask the user to set up network channels to allow connectivity from outside the cloud provider (i.e., the internet) since by default these services only allow ingress and egress connectivity from the VPC that holds the cluster. This can lead to provider lock-in because the applications have no other option other than being co-located with the cluster. Though setting up network channels is an option, that does not come for free.

Another characteristic of partially managed services is that they grant users access to the guts of the cluster. One might be able to SSH into the compute instance that runs the broker, or even change the encryption keys that persistent volumes (used by the brokers for persistence) require to implement security at rest. In this context, though the cluster might have been automatically created by the provider, the user can change the settings directly. For some, this might seem like a good thing, but in reality it increases co-responsibility.

Partially managed services can be easily spotted by the fact that they lack a good story about users, groups, and permissions. If you look at this Go program, the program connects to the cluster in Confluent Cloud using an API key and secret instead of a username and password. This is a best practice for managed services that are accessed from thousands of applications and minimizes the burden from the user when it comes to maintaining databases for credentials.

Most partially managed services offer Apache Kafka as is so that the user is responsible for setting up authentication at a broker level. This significantly increases the complexity of having a managed service, because the user has to implement details that should be transparent to them. Once again, this falls into the co-responsibility model that we discussed before.

Finally, partially managed services ask users to manage all aspects of the distributed streaming platform beyond the Kafka cluster and what is included natively. Users must install, manage, and operate technologies from the Kafka ecosystem, such as Confluent Schema Registry, Kafka Connect, Kafka Streams, ksqlDB, etc. Although they say that their service is fully compatible with these technologies, the reality is that it’s another example of partially managed services relying on the co-responsibility model.

At this point, you should be fully equipped to spot a truly managed service by simply eliminating all options that may look like a hosted solution or a partially managed service.

Top five characteristics of a fully managed service

If you have reached this part of the blog, perhaps you have a few managed services for Apache Kafka in mind and you want to know which one you should choose. This section provides the top five characteristics that every fully managed service for Apache Kafka must have, so you can more confidently evaluate which ones are worth your time and money.

1. Serverless computing model

If you’ve read about any strategies on how to succeed with cloud, then you know that the ability to scale up and down computing resources harmonically as needed is by far the key to keeping costs low. In this context, harmonically refers to scaling up and down each resource in respect to their unique usage of computing resources. Furthermore, the user resources don’t need to be available by the time they are requested, and when there is no usage of the managed service, the resources are disposed of accordingly. Inability to do so results in a fixed cost for those resources and causes waste.

To better understand this, it is important to know which resources are necessary while deploying Kafka clusters in a given cloud provider. At a very minimum, you will need:

- Compute: the instances that host your Kafka brokers and ZooKeeper

- Storage: each instance will likely have non-ephemeral disks attached to it

- Network: though you usually don’t pay for VPCs, there are bandwidth costs

Besides the minimum, other resources that may be necessary for your deployment include load balancers, SSL certificates, metrics and logs, NAT gateways (if each compute instance requires superior egress throughput), and encryption keys. Failure to plan ahead about how much you will use each of these resources will end up in oversizing to ensure that your deployment never runs out of capacity. Even if you plan ahead, sizing is a moving target. It often changes as your deployment encounters new requirements, or because quality attributes change, such as the need for more resiliency, fault-tolerance, security, etc.

Sizing is the art of measuring each component of architecture and understanding what the ratio of growth and shrinkage of that component is when there is a need to scale up and down. The scaling process can’t be the same for each component, because that would cause even more waste. Doubling the capacity of a Kafka cluster to handle write throughput is not just multiplying each individual component of its architecture by “n” (“n” being the representation of some empirical unit of scale), because each component behaves differently in regard to computing resources.

Hence, all the resources need to scale up and down harmonically. A deep understanding of how the cloud provider works, as well as how the software architecture (in this case, Apache Kafka) works in terms of computing resources consumption is necessary for accomplishing this.

Understanding cloud provider limits also ensures that seasonal workloads will not create situations that prevent you from spinning up a new cluster, for example, because the number of VPCs created exceed what is permitted by default. When limits have to be increased in the cloud provider, billing costs may also increase and the time taken to scale out the service may take longer as well. Limits make planning sizing ahead even more important.

Confluent Cloud Basic and Standard clusters address elasticity with a pricing model that is usage based, in which the user pays only for the data that is actually streamed. If there is no traffic in any of the created clusters, then there are no charges (excluding data storage costs). Usage is calculated solely based on ingress data, egress data, and storage. Confluent Cloud Basic and Standard clusters scale from zero to 100 MBps at any time.

Another nice thing about Confluent Cloud is that it owns the resources used for clusters, freeing users from having to know (or more accurately, to guess) how to create and scale resources harmonically. In other words, Confluent Cloud is a truly serverless service for Apache Kafka.

Figure 5. Users can benefit from serverless Apache Kafka with Confluent Cloud.

| Note: Standard clusters support up to 100 MBps of throughput. If you need more, Confluent Cloud Dedicated clusters support GBps scale. | ||

Elasticity is required not only for clusters but also for all the technologies that developers need to implement event streaming applications, such as Kafka Connect, Schema Registry, and Kafka Streams. A managed service ought to support these technologies without asking the user to take care of them individually.

2. One-stop shop for event streaming applications

As discussed before, Apache Kafka is a distributed streaming platform comprised of messaging, storage, and stream processing. By translating this into concrete technologies, you will find that Apache Kafka is made up of:

- Core Kafka: brokers that implement messaging and storage capabilities

- Clients API: framework for creating producers (writers) and consumers (readers)

Although this is an organized way of breaking down the technologies that make up Kafka, handling each of them as part of a distributed streaming platform is hard. Oftentimes, developers create multiple deployment silos for each one, requiring different implementation efforts. But a good managed service for Apache Kafka provides a consistent, integrated, and easy-to-use way for developers to use these technologies—they should not be managed separately. Any time a provider tells the user to take care of any one of those technologies on their own is a strong indication that the service is partially managed.

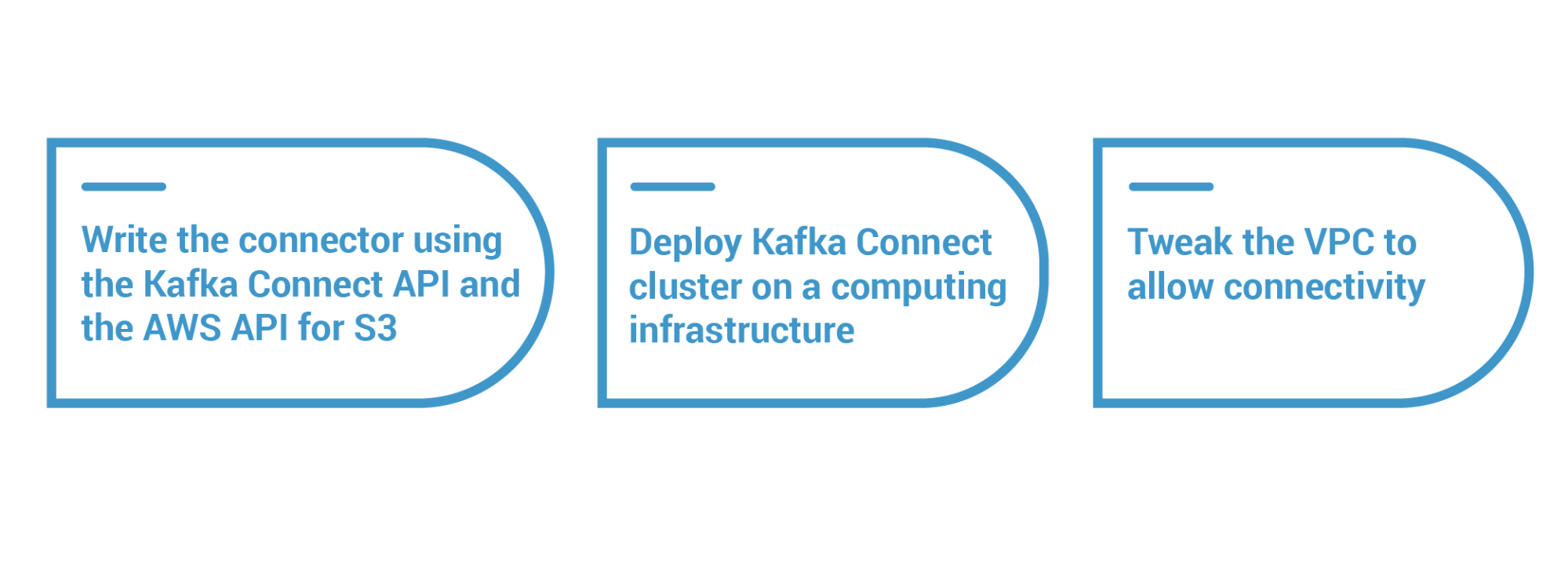

To better understand this, let’s walk through a scenario that shows a common implementation of Apache Kafka in the cloud. Imagine that a developer needs to send records from a topic to an S3 bucket in AWS. The appropriate implementation would be to use a connector running on Kafka Connect. The connector then periodically fetches records from topic partitions and writes them into the S3 bucket. Here are the tasks for this implementation:

Figure 6. Implementation effort to send records from a topic to an AWS S3 bucket

As you can see in Figure 6, there are at least three moving parts, each of which has a cost associated with it. When we refine the diagram to display that element, here is what we get:

Figure 7. Implementation effort refined to include the element of cost

As you can see, not only is there a significant amount of dollars needed to build this, but there are also other costs involved like time. This includes learning how the APIs works for both the Kafka Connect and AWS S3 APIs, writing the actual code for the connector, and maintaining the connector as the APIs for Kafka Connect and AWS S3 change (i.e., updating, testing, and redeploying it).

That’s just part of the cost. Developers also need to work on the other moving parts like managing the Kafka Connect cluster where the connector is deployed. This is no easy task. Creating and maintaining clusters for Kafka Connect includes tedious, error-prone tasks like downloading the bits of Kafka Connect, creating compute instances and storage to install the bits, setting up the connector, configuring Kafka Connect for scalability and fault-tolerance using the distributed mode, and tweaking the VPC to enable connectivity to the Kafka cluster.

This last task may be as “simple” as setting up route-tables, firewalls, and subnets if Kafka Connect is co-located in the same VPC that the Kafka cluster also runs—but it may require a more complex setup like VPC peering if they belong to different VPCs.

Even if you automate the lifecycle of Kafka Connect and the connector deployment through infrastructure-as-code technologies (e.g., Terraform, Ansible, or Puppet), the cost of cloud resources still applies. For this scenario, you would pay for compute instances and storage, likely more than needed in order to ensure a minimum level of reliability.

| Note: automation of resources using infrastructure as code, as the name implies, is still coding, and therefore should not be treated as if there was no coding at all. Infrastructure as code typically leads to a development effort that is just as hard as performing tasks manually since it requires a deep understanding of what is being created in the given cloud provider. | ||

Fortunately, scenarios like the one described above can be implemented in an easy way. Confluent Cloud, for example, provides out-of-the-box connectors so developers don’t need to spend time creating and maintaining their own. There are dozens of different connectors available, including Postgres, MySQL, Oracle cloud storage (GCP Cloud Storage, Azure Blob Storage, and AWS S3), cloud functions (AWS Lambda, Google Cloud Functions, and Azure Functions), Snowflake, Elasticsearch, and more.

More importantly, Confluent Cloud provides Kafka Connect as a service, which means that there is no need for users to maintain Kafka Connect clusters on their own. By using a truly serverless approach, you can be more agile and focused on your work.

Figure 8. Native support for Kafka Connect and the Amazon S3 Data Sink connector in Confluent Cloud

In addition to the Kafka bits, a managed service should also provide tools that make your life easier during implementation. For example, instead of simply asking you to use the Kafka Streams API in your own Java applications, a managed service should provide a way to implement streaming processing in a much faster runtime with ksqlDB. Confluent Cloud provides built-in support for ksqlDB, where you can deploy continuous queries using the same serverless experience offered for Kafka clusters and Kafka Connect.

Figure 9. Native support for ksqlDB in Confluent Cloud

Thanks to the SQL-like syntax of ksqlDB, there is no need to write Java code, and because the code will execute in the managed service, there is no extra cost with compute instances and storage.

Also, there is built-in support for Schema Registry in Confluent Cloud, so event pipelines that require schema management, evolution, and enforcement can be easily implemented as well.

Figure 10. Native support for Schema Registry in Confluent Cloud

In summary, the managed service should be a one-stop shop for event streaming applications. It should provide all the tools needed to build event streaming applications with no need to look anywhere else.

3. Support provided by Apache Kafka experts

There’s no question that Apache Kafka is a popular open source project with an extremely bright and vibrant community worldwide that makes it what it is. With the technology changing very fast, however, it is hard to become an expert if you are not directly involved with the project as a committer or member of the community who actively attends conferences, joins meetups, and participates in social media.

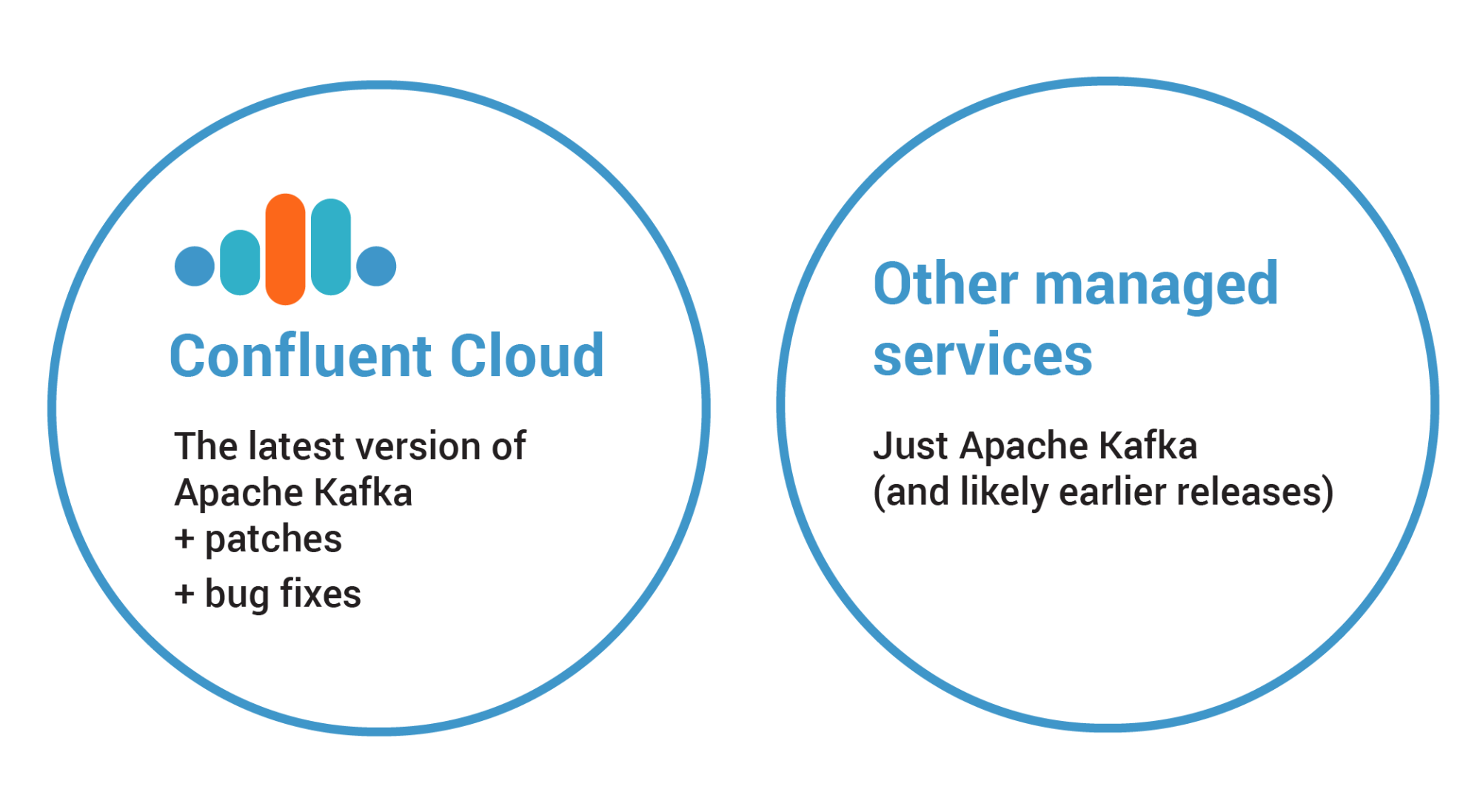

Most managed services are based on the last official release of Apache Kafka. This seems reasonable because it will contain the latest features and bug fixes, but it does not guarantee that the managed service will be stable, since running the software in the cloud brings unique challenges as previously discussed. Stability comes when the source code is battle tested against production-like environments, which in turn shapes technical decisions around changing the source code if limitations are found. Applying these changes in the codebase used by a managed service in production requires a deep understanding of Apache Kafka and, therefore, experts from the engineering team.

Continuing with our previous example, Confluent Cloud is based on a codebase that is ahead of the last official release of Apache Kafka. The bits running in production come from a branch that contains the source code from the master branch of Apache Kafka, merged with stable snapshots upstream, as well as plugins and add-ons that Confluent builds to operate Confluent Cloud flawlessly. Moreover, the bits include any changes made in the source code that were the result of the battle-proven tests mentioned earlier. By using this strategy, we solve different problems related to stability that would not be possible if we had to wait for the next stable release of Kafka.

The first problem solved with this strategy is performing rolling upgrades to a new Apache Kafka version quickly. If you run a codebase that is ahead of the last official release, then the time necessary to upgrade your clusters is minimal, since any issues found during the normal upgrade process have been solved already. The second improvement is a faster bug fix cycle. You don’t have to wait for the next official release of Kafka and avoid getting stuck due to bugs in the software.

Figure 11. Confluent Cloud runs with a codebase that is more stable than the last official release.

Using managed services that are backed by experts also means a superior support experience. Per usual, you can file support tickets about issues with the operation of the service, but there also might be situations where you want to ask advanced questions related to the core technology and how it can be tuned to optimize application performance. While arguably all managed services might provide a channel for things like this, the ones with Apache Kafka experts are more qualified to provide detailed and effective answers in a timely manner.

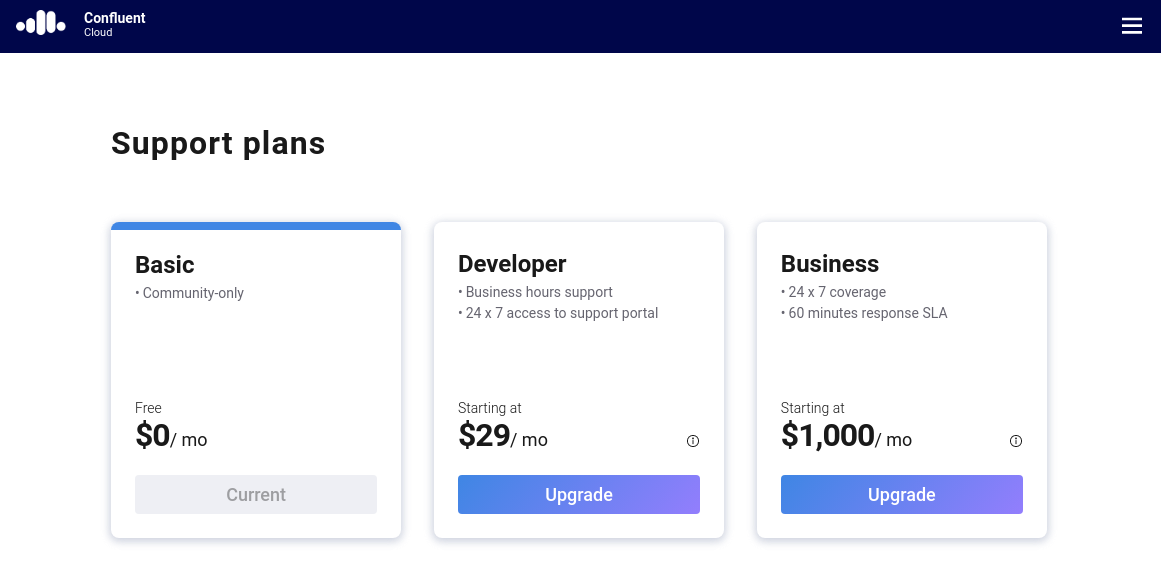

Confluent provides the best support service for Apache Kafka on the planet, but what few people know is that you can have this for Confluent Cloud too.

Figure 12. Users can upgrade their account to obtain support from Confluent.

The interesting part about this approach is that Confluent doesn’t force you into a paid support plan. You are absolutely free to remain on the basic plan which is included by default. Users that are interested in having Confluent back their event streaming applications can optionally select a plan that suits their needs. To upgrade, simply click on the button found in the top right part of the UI (the button known as hamburger menu) and select “Support plans.”

Another benefit of using managed services backed by Kafka experts is the ability to use technologies beyond Apache Kafka. Perhaps you need to implement a feature in your Go program that depends on the idempotent producer. This feature is available for Java clients because it is part of the reference implementation for Apache Kafka, but you would have to introduce this functionality to your Go client. You would miss project deadlines due to technical difficulties.

The scenario presented could be easily addressed with a managed service that provides native clients for different programming languages, beyond what is provided by Apache Kafka. This would require real Apache Kafka experts developing these native clients, keeping them up to date with new features in Apache Kafka, as well as collaborating with support teams when asked technical questions about these clients. Just like before, this goes beyond merely offering Kafka clusters as a service.

Confluent Cloud provides native clients for programming languages like Java, C/C++, Go, .NET, Python, and Scala. All these clients are developed and supported by Confluent, which has an engineering team dedicated to this.

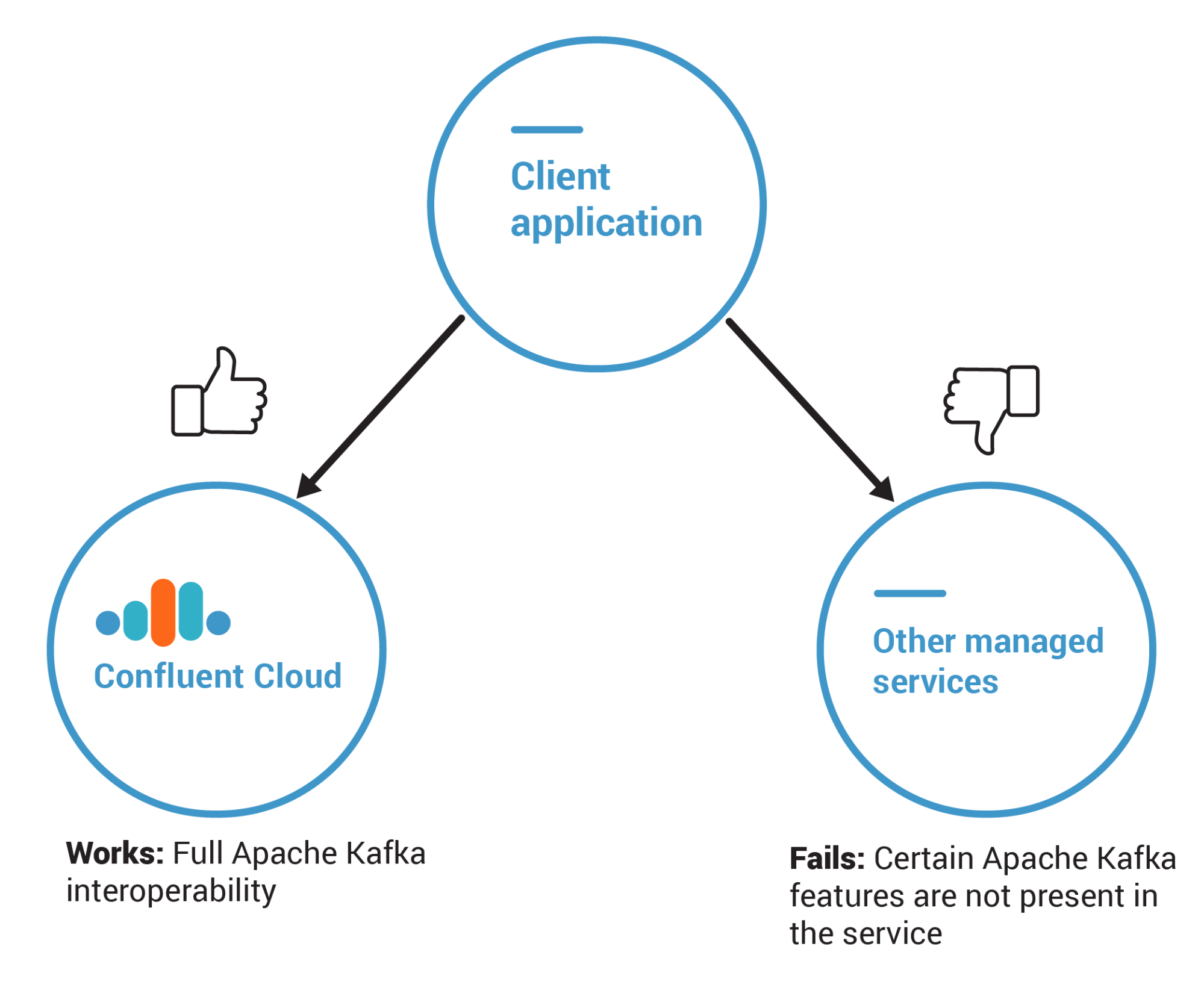

4. Apache Kafka interoperability

It should be unnecessary to say that all managed services must provide full interoperability with Apache Kafka, but unfortunately, it isn’t. Interoperability refers to full support for common tools and frameworks used by developers working with Apache Kafka and all its features.

When building applications, implementing code that relies on specific features of Apache Kafka is inevitable. To prevent duplication of records during transmission from the client to the broker, you will likely enable the idempotent producer feature. You might also enable support for transactions by writing code that performs writes to multiple topics and partitions atomically, as well as writing code to ensure that consumers will only read records that have been committed.

For the written code to leverage all these features, the application must connect to a full-fledged Kafka cluster. For managed services that are not based on Apache Kafka, any application connecting to them will not be able to leverage the features. As much as possible, explore a managed service’s support options for Kafka before the project starts to avoid refactoring your code to overcome the limitation.

Certain providers that have proprietary messaging technologies provide proxies for Kafka clients to enable client connectivity. While this may seem shiny from the outside, their interoperability with Apache Kafka is deficient. Developers are sometimes are told to stick with the managed services offered natively by the company’s chosen provider and therefore must comply.

However, decisions like this should be revisited if the team feels that what the provider has to offer is not enough and might cause future technical debts of refactoring the code. The team should then prove to the company that it will be less expensive than using another managed service because it ensures that no code will have to be refactored. Though this sounds simple in theory, proving it often requires building prototypes that lack interoperability.

To speed things up, ask the provider for a code example that demonstrates the usage of a required feature. They may formally notify you that their managed service does not support that feature because what they provide is simply a proxy that translates client requests made to their messaging platform using the Kafka client API. It’s your best resource to prove that using another managed service is the solution.

Figure 13. Managed services that are not based on Apache Kafka lack important features.

Having to use different tools and frameworks is another aspect to watch out for. Some providers include the Apache Kafka APIs with their proprietary SDK as an attempt to create lock-in. In their minds, if you use their SDK while building applications, then you will be so tightly coupled with the provider and leaving them will be harder.

This is effective, because some developers blindly believe that using the provider’s SDK will save them the hassle of thinking about code optimization, code performance, and development best practices. Although sometimes the SDK might actually provide all of this, it still leads to tight coupling with the provider. As a best practice, you should use the tools and frameworks provided by Apache Kafka to avoid provider lock-in and ensure more productivity by reusing the same tools and frameworks on premises. There are many resources out there that help you do this, including this post on how to use Kafka tools to connect to clusters running on Confluent Cloud.

Confluent Cloud provides full-fledged Kafka clusters so that client applications can leverage all the features from the technology. Moreover, the code written by developers is the same one written for Kafka clusters running on premises; thus, there is no requirement to learn different tools and frameworks.

Besides the problems discussed thus far, certain providers may have other subtle limitations, such as handling throttling rules related to how often a consumer can commit offsets for a given partition. In this context, the provider throttles commit offset attempts that extrapolate the minimum of X commits per second, queueing them so they don’t overflow the managed service. The consequence is having to change the code to bring the throttling logic to the application—or even worse—having to change the code to commit the offsets asynchronously, which could in turn lead into other collateral problems if the code has to ensure consistency while consuming the records.

5. No cloud provider lock-in

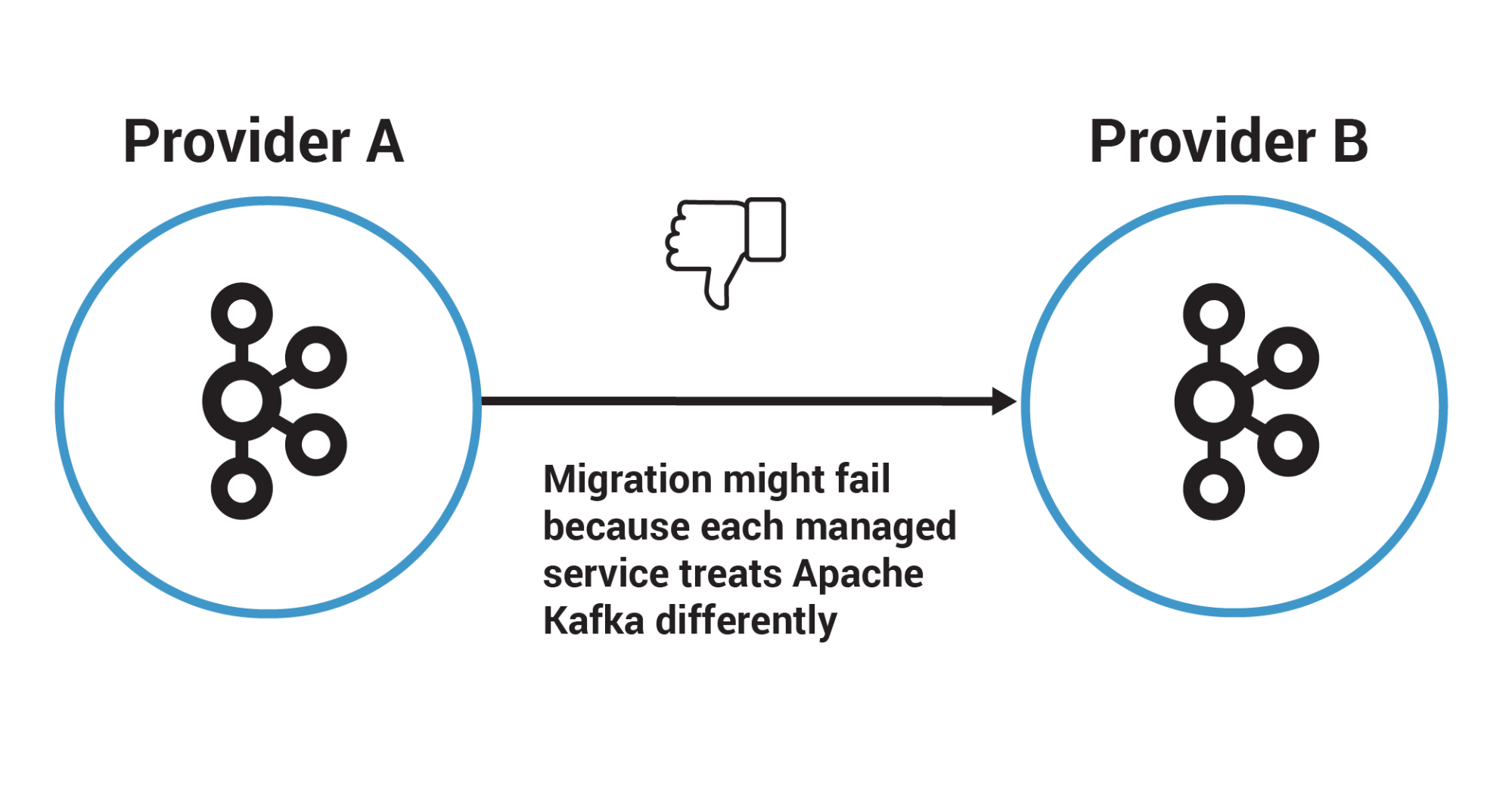

The problem of vendor lock-in predates cloud computing, and people are generally aware of its consequences. But the issue is worse than it seems due to the nature of cloud. Providing a way for developers to implement applications without having to worry about infrastructure and platform details diminishes their ability to fully understand how locked in they actually are. It becomes impossible to evaluate how much time it will take to migrate your applications from one provider to another because there is no clear understanding of which parts are deeply tied to the provider.

Users nowadays are even more concerned and may avoid a specific cloud provider altogether if there are any red flags around leaving one provider for another. For this reason, it’s important that managed services for Apache Kafka offer support for different cloud providers. More importantly, it should be possible to move away from one cloud provider without any technical barriers.

For example, imagine that there’s a team of developers who need to build a cloud-based application. This application relies on Apache Kafka to deliver certain event streaming capabilities, so they decide to use the managed service that their chosen provider offers in its portfolio, instead of looking for one that avoids provider lock-in. This managed service implements authentication using certificates, which means that any client connecting to the Kafka cluster will have to import the client credentials from the certificate. Now, imagine that the team is then told to migrate the application to another provider because of some new corporate directive, such as an acquisition, merger, or because the costs with this other provider are lower.

They start the migration process to the other provider, which should be smooth since it is all Apache Kafka, right? First, they use the same approach of using what the new provider offers in its portfolio. Secondly, they migrate the data from the topics, a task that they will likely accomplish by using MirrorMaker or Confluent Replicator to replicate the data while the source and target clusters run side by side. Third, they perform comprehensive tests in the application to make sure that nothing is broken due to the migration.

Now here comes the bummer. The new managed service doesn’t implement authentication with certificates but instead uses credential pairs. This impacts all clients that need to connect with the Kafka cluster, including the application itself. Unsurprisingly, this delays the team’s ability to migrate the application, and requires them to refactor their code to start leveraging the credential pairs provided by the new managed service.

Figure 14. Managed services should promote a consistent developer experience across cloud providers.

Situations like this can be avoided by using managed services that treat Apache Kafka equally across different cloud providers. To do this, these managed services support multiple cloud providers, as well as ensure that the developer experience is the same across them. The latter is even more complicated to deliver than the former, because ensuring that the developer experience is the same across cloud providers requires many levels of abstraction to be in place, and this is hard to implement.

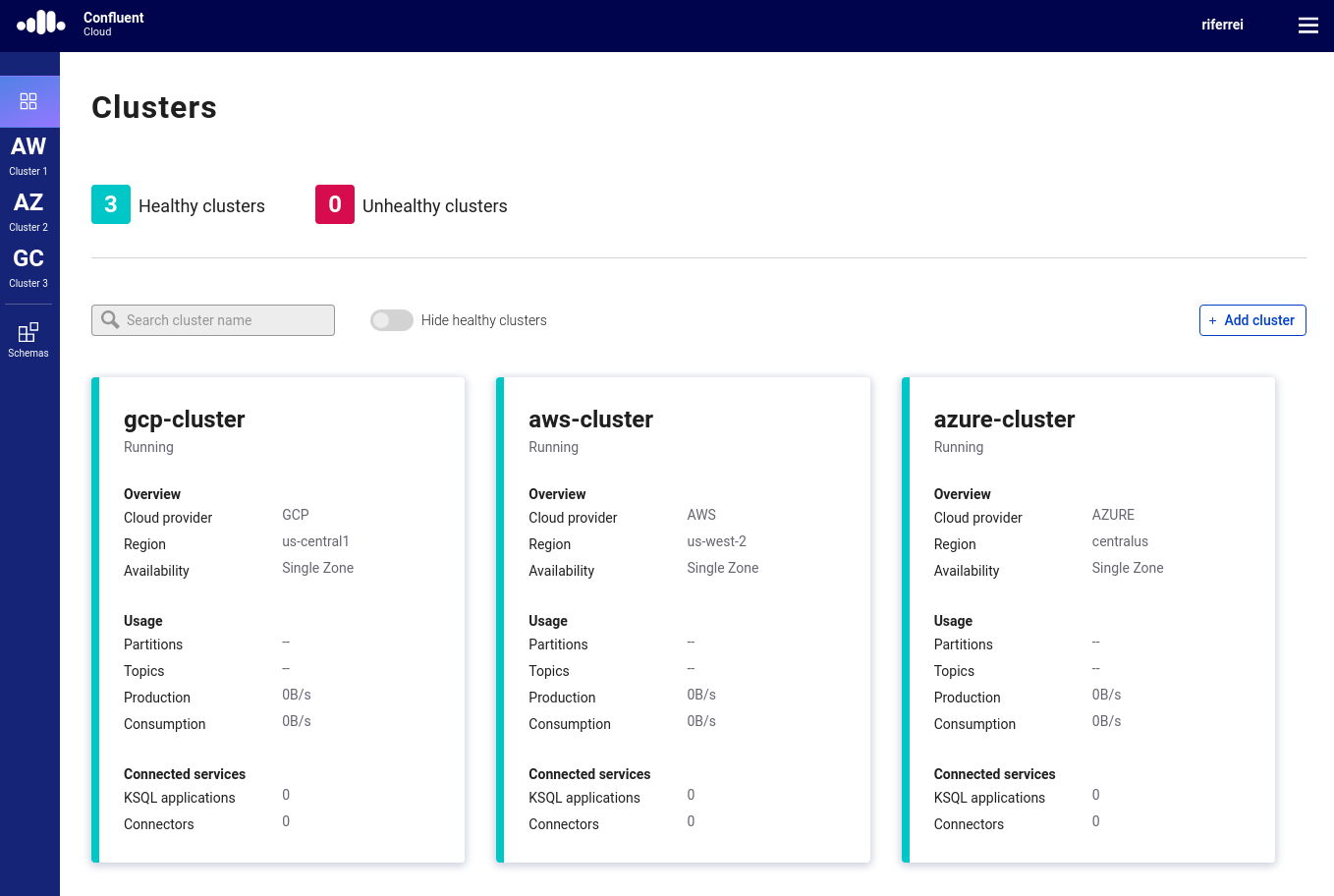

Confluent Cloud delivers this beautifully. It not only supports major cloud providers such as GCP, Azure, and AWS, but it also ensures that the developer’s experience is exactly the same in all of them. Users are welcome to choose from any of these cloud providers and at the same time can have multiple clusters, with each one running on a different cloud provider.

Figure 15. Confluent Cloud supports clusters running on different cloud providers.

This fundamentally changes how Apache Kafka is used in the cloud because now users can choose which cloud provider to work with purely based on their cost, while the experience of how they will connect to clusters, build applications, migrate data, and monitor the managed service is exactly the same.

One thing to note is that some companies would like to use services like Confluent Cloud that support all major cloud providers, but as if they were a native service from one of the cloud providers. Supporting multiple cloud providers avoids the problem of lock-in, but it may incidentally create other operational problems like different bills, as well as dealing with different support teams.

To avoid problems like this, Confluent Cloud can be purchased through the cloud provider marketplaces on AWS, Google Cloud or Azure, so your Confluent Cloud usage appears on your cloud provider bill. Confluent also has a partnership with Google to make Confluent Cloud work even more like a native service on GCP.

Summary

The journey to unlocking the benefits of event streaming can be long and painful due to the infrastructure challenges that this architectural style may bring. This is true especially if the plan is to implement event streaming applications in the cloud. Luckily, services such as Confluent Cloud provide a complete, fully managed, serverless, and easy-to-use event streaming platform built on top of Apache Kafka that allows developers to be focused on what they do best: developing applications.

This blog post has provided the key points you need to identify and evaluate a true managed service for Kafka. As a next step, I invite you to experiment with Confluent Cloud and try out the examples from this GitHub repository. There are examples written in many programming languages, and they will give you the boost you need to start streaming without worrying about infrastructure details.

Ready to start?

To learn more, sign up for Confluent Cloud today and start streaming with the best managed service for Apache Kafka. If you’re a new user, you’ll receive $400 to spend within Confluent Cloud during your first 60 days. You can also use the promo code CL60BLOG for an additional $60 of free Confluent Cloud usage.*

Avez-vous aimé cet article de blog ? Partagez-le !

Abonnez-vous au blog Confluent

New With Confluent Platform 8.0: Stream Securely, Monitor Easily, and Scale Endlessly

This blog announces the general availability (GA) of Confluent Platform 8.0 and its latest key features: Client-side field level encryption (GA), ZooKeeper-free Kafka, management for Flink with Control Center, and more.

Introducing the Next Generation of Control Center for Confluent Platform: Enhanced UX, Faster Performance, and Unparalleled Scale

This blog announces the general availability of the next generation of Control Center for Confluent Platform