Apache Kafka®️ 비용 절감 방법 및 최적의 비용 설계 안내 웨비나 | 자세히 알아보려면 지금 등록하세요

Bottled Water: Real-time integration of PostgreSQL and Kafka

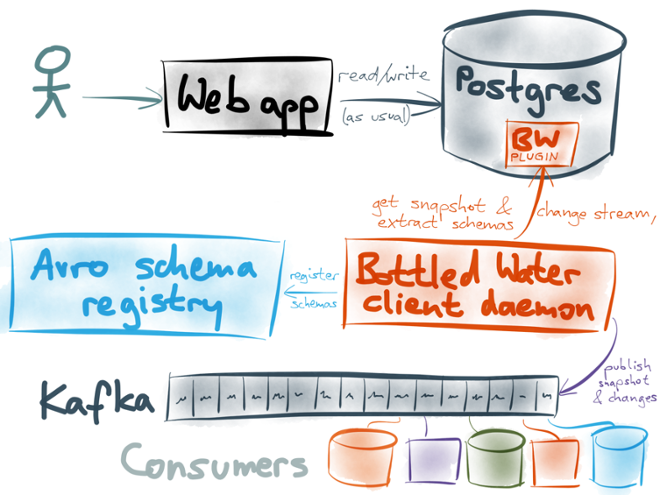

Summary: Confluent is starting to explore the integration of databases with event streams. As part of the first step in this exploration, Martin Kleppmann has made a new open source tool called Bottled Water. It lets you transform your PostgreSQL database into a stream of structured Kafka events. This is tremendously useful for data integration.

Writing to a database is easy, but getting the data out again is surprisingly hard.

Of course, if you just want to query the database and get some results, that’s fine. But what if you want a copy of your database contents in some other system — for example, to make it searchable in Elasticsearch, or to pre-fill caches so that they’re nice and fast, or to load it into a data warehouse for analytics, or if you want to migrate to a different database technology?

If your data never changed, it would be easy. You could just take a snapshot of the database (a full dump, e.g. a backup), copy it over, and load it into the other system. The problem is that the data in the database is constantly changing, and so the snapshot is already out-of-date by the time you’ve loaded it. Even if you take a snapshot once a day, you still have one-day-old data in the downstream system, and on a large database those snapshots and bulk loads can become very expensive. Not really great.

So what do you do if you want a copy of your data in several different systems?

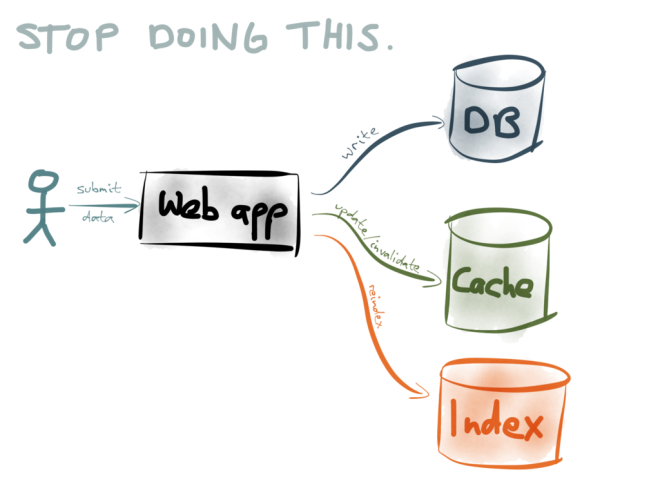

One option is for your application to do so-called “dual writes”. That is, every time your application code writes to the database, it also updates/invalidates the appropriate cache entries, reindexes the data in your search engine, sends it to your analytics system, and so on: However, as I explain in one of my talks, the dual-writes approach is really problematic. It suffers from race conditions and reliability problems. If slightly different data gets written to two different datastores (perhaps due to a bug or a race condition), the contents of the datastores will gradually drift apart — they will become more and more inconsistent over time. Recovering from such gradual data corruption is difficult.

However, as I explain in one of my talks, the dual-writes approach is really problematic. It suffers from race conditions and reliability problems. If slightly different data gets written to two different datastores (perhaps due to a bug or a race condition), the contents of the datastores will gradually drift apart — they will become more and more inconsistent over time. Recovering from such gradual data corruption is difficult.

If you rebuild a cache or index from a snapshot of a database, that has the advantage that any inconsistencies get blown away when you rebuild from a new database dump. However, on a large database, it’s slow and inefficient to process the entire database dump once a day (or more frequently). How could we make it fast?

Typically, only a small part of the database changes between one snapshot and the next. What if you could process only a “diff” of what changed in the database since the last snapshot? That would also be a smaller amount of data, so you could take such diffs more frequently. What if you could take such a “diff” every minute? Every second? 100 times a second?

When you take it to the extreme, the changes to a database become a stream. Every time someone writes to the database, that is a message in the stream. If you apply those messages to a database in exactly the same order as the original database committed them, you end up with an exact copy of the database. And if you think about it, this is exactly how database replication works.

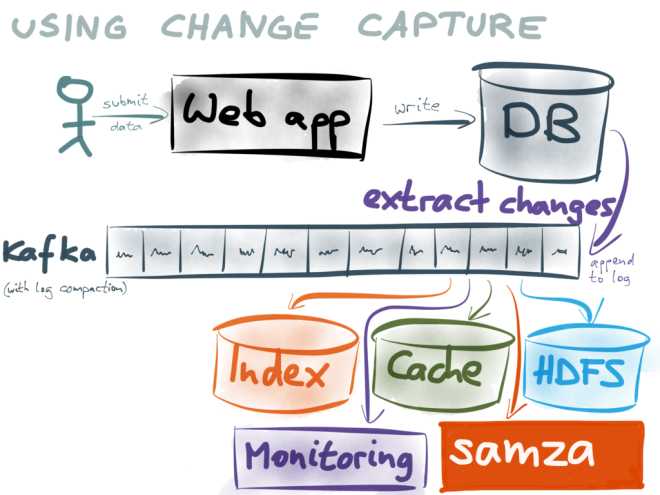

The replication approach to data synchronization works much better than dual writes. First, you write all your data to one database (which is probably what you’re already doing anyway). Next, you extract two things from that database:

- a consistent snapshot at one point in time, and

- a real-time stream of changes from that point onwards.

You can load the snapshot into the other systems (for example your search indexes or caches), and then apply the real-time changes on an ongoing basis. If this pipeline is well tuned, you can probably get a latency of less than a second, so your downstream systems remain very almost up-to-date. And since the stream of changes provides ordering of writes, race conditions are much less of a problem.

This approach to building systems is sometimes called Change Data Capture (CDC), though the tools for doing it are currently not very good. However, at some companies, CDC has become a key building block for applications — for example, LinkedIn built Databus and Facebook built Wormhole for this purpose.

I am excited about change capture because it allows you to unlock the value in the data you already have. You can feed the data into a central hub of data streams, where it can readily be combined with event streams and data from other databases in real-time. This approach makes it much easier to experiment with new kinds of analysis or data format, it allows gradual migration from one system to another with minimal risk, and it is much more robust to data corruption: if something goes wrong, you can always rebuild a datastore from the snapshot and the stream.

Getting the real-time stream of changes

Getting a consistent snapshot of a database is a common feature, because you need it in order to take backups. But getting a real-time stream of changes has traditionally been an overlooked feature of databases. Oracle GoldenGate, the MySQL binlog, the MongoDB oplog or the CouchDB changes feed do something like this, but they’re not exactly easy to use correctly. More recently, a few databases such as RethinkDB or Firebase have oriented themselves towards real-time change streams.

However, today we will talk about PostgreSQL. It’s an old-school database, but it’s good. It is very stable, has good performance, and is surprisingly full-featured.

Until recently, if you wanted to get a stream of changes from Postgres, you had to use triggers. This is possible (see below), but it is fiddly, requires schema changes and doesn’t perform very well. However, Postgres 9.4 (released in December 2014) introduced a new feature that changes everything: logical decoding (which I explain in more detail below).

With logical decoding, change data capture for Postgres suddenly becomes much more appealing. So, when this feature was released, I set out to build a change data capture tool for Postgres that would take advantage of the new facilities. Confluent sponsored me to work on it (thank you Confluent!), and today we are releasing an alpha version of this tool as open source. It is called Bottled Water. Introducing Bottled Water

Introducing Bottled Water

Logical decoding takes the database’s write-ahead log (WAL), and gives us access to row-level change events: every time a row in a table is inserted, updated or deleted, that’s an event. Those events are grouped by transaction, and appear in the order in which they were committed to the database. Aborted/rolled-back transactions do not appear in the stream. Thus, if you apply the change events in the same order, you end up with an exact, transactionally consistent copy of the database.

The Postgres logical decoding is well designed: it even creates a consistent snapshot that is coordinated with the change stream. You can use this snapshot to make a point-in-time copy of the entire database (without locking — you can continue writing to the database while the copy is being made), and then use the change stream to get all writes that happened since the snapshot.

Bottled Water uses these features to copy all the data in a database, and encodes it in the efficient binary Avro format. The encoded data is sent to Kafka — each table in the database becomes a Kafka topic, and each row in the database becomes a message in Kafka.

Once the data is in Kafka, you can easily write a Kafka consumer that does whatever you need: send it to Elasticsearch, or populate a cache, or process it in a Samza job, or load it into HDFS with Camus… the possibilities are endless.

Why Kafka?

Kafka is a messaging system, best known for transporting high-volume activity events, such as web server logs and user click events. In Kafka, such events are typically retained for a certain time period and then discarded. Is Kafka really a good fit for database change events? We don’t want database data to be discarded!

In fact, Kafka is a perfect fit — the key is Kafka’s log compaction feature, which was designed precisely for this purpose. If you enable log compaction, there is no time-based expiry of data. Instead, every message has a key, and Kafka retains the latest message for a given key indefinitely. Earlier messages for a given key are eventually garbage-collected. This is quite similar to new values overwriting old values in a key-value store.

Bottled Water identifies the primary key (or replica identity) of each table in Postgres, and uses that as the key of the messages sent to Kafka. The value of the message depends on the kind of event:

- For inserts and updates, the message value contains all of the row’s fields, encoded as Avro.

- For deletes, the message value is set to null. This causes Kafka to remove the message during log compaction, so its disk space is freed up.

With log compaction, you don’t need one system to store the snapshot of the entire database and another system for the real-time messages — they can live perfectly well within the same system. Bottled Water writes the initial snapshot to Kafka by turning every single row in the database into a message, keyed by primary key, and sending them all to the Kafka brokers. When the snapshot is done, every row that is inserted, updated or deleted similarly turns into a message.

If a row frequently gets updated, there will be many messages with the same key (because each update turns into a message). Fortunately, Kafka’s log compaction will sort this out, and garbage-collect the old values, so that we don’t waste disk space. On the other hand, if a row never gets updated or deleted, it just stays unchanged in Kafka forever — it never gets garbage-collected.

Having the full database dump and the real-time stream in the same system is tremendously powerful. If you want to rebuild a downstream database from scratch, you can start with an empty database, start consuming the Kafka topic from the beginning, and scan through the whole topic, writing each message to your database. When you reach the end, you have an up-to-date copy of the entire database. What’s more, you can continue keeping it up-to-date by simply continuing to consume the stream. Building alternative views onto your data was never easier!

The idea maintaining a copy of your database in Kafka surprises people who are more familiar with traditional enterprise messaging and its limitations. Actually, this use case is exactly why Kafka is built around a replicated log abstraction: it makes this kind of large-scale data retention and distribution possible. Downstream systems can reload and re-process data at will, without impacting the performance of the upstream database that is serving low-latency queries.

Why Avro?

The data extracted from Postgres could be encoded as JSON, or Protobuf, or Thrift, or any number of formats. However, I believe Avro is the best choice. Gwen Shapira has written about the advantages of Avro for schema management, and I’ve got a blog post comparing it to Protobuf and Thrift. The Confluent stream data platform guide gives some more reasons why Avro is good for data integration.

Bottled Water inspects the schema of your database tables, and automatically generates an Avro schema for each table. The schemas are automatically registered with Confluent’s schema registry, and the schema version is embedded in the messages sent to Kafka. This means it “just works” with the stream data platform’s serializers: you can work with the data from Postgres as meaningful application objects and rich datatypes, without writing a lot of tedious parsing code.

The translation of Postgres datatypes into Avro is already fairly comprehensive, covering all the common datatypes, and providing a lossless and sensibly typed conversion. I intend to extend it to support all of Postgres’ built-in datatypes (of which there are many!) — it’s some effort, but it’s worth it, because good schemas for your data are tremendously important.

The logical decoding output plugin

An interesting property of Postgres’ logical decoding feature is that it does not define a wire format in which change data is sent over the network to a consumer. Instead, it defines an output plugin API, which receives a function call for every insert, update or delete. Bottled Water uses this API to read data in the database’s internal format, and serializes it to Avro.

The output plugin must be written in C using the Postgres extension mechanism, and loaded into the database server as a shared library. This requires superuser privileges and filesystem access on the database server, so it’s not something to be undertaken lightly. I understand that many a database administrator will be scared by the prospect of running custom code inside the database server. Unfortunately, this is the only way logical decoding can currently be used.

At the moment, the logical decoding plugin must be installed on the leader database. In principle, it would be possible to have it run on a separate follower, so that it cannot impact other clients, but the current implementation in Postgres does not allow this. This limitation will hopefully be lifted in future versions of Postgres.

The client daemon

Besides the plugin (which runs inside the database server), Bottled Water consists of a client program which you can run anywhere. It connects to the Postgres server and to the Kafka brokers, receives the Avro-encoded data from the database, and forwards it to Kafka.

The client is also written in C, because it’s easiest to use the Postgres client libraries that way, and because some code is shared between the plugin and the client. It’s fairly lightweight and doesn’t need to write to disk.

What happens if the client crashes, or gets disconnected from either Postgres or Kafka? No problem. It keeps track of which messages have been published and acknowledged by the Kafka brokers. When the client restarts after an error, it replays all messages that haven’t been acknowledged. Thus, some messages could appear twice in Kafka, but no data should be lost.

Related work

Various other people are working on similar problems:

- Decoderbufs is an experimental Postgres plugin by Xavier Stevens that decodes the change stream into a Protocol Buffers format. It only provides the logical decoding plugin part of the story — it doesn’t have the consistent snapshot or client parts (Xavier mentions he has written a client which reads from Postgres and writes to Kafka, but it’s not open source).

- pg_kafka (also from Xavier) is a Kafka producer client in a Postgres function, so you could potentially produce to Kafka from a trigger.

- PGQ is a Postgres-based queue implementation, and Skytools Londiste (developed at Skype) uses it to provide trigger-based replication. Bucardo is another trigger-based replicator. I get the impression that trigger-based replication is somewhat of a hack, requiring schema changes and fiddly configuration, and incurring significant overhead. Also, none of these projects seems to be endorsed by the PostgreSQL core team, whereas logical decoding is fully supported.

- Sqoop recently added support for writing to Kafka. To my knowledge, Sqoop can only take full snapshots of a database, and not capture an ongoing stream of changes. Also, I’m unsure about the transactional consistency of its snapshots.

- For those using MySQL, James Cheng has put together a list of change capture projects that get data from MySQL into Kafka. AFAIK, they all focus on the binlog parsing piece and don’t do the consistent snapshot piece.

Status of Bottled Water

At present, Bottled Water is alpha-quality software. It’s more than a proof of concept — quite a bit of care has gone into its design and implementation — but it hasn’t yet been tested in any real-world scenarios. It’s definitely not ready for production use right now, but with some testing and tweaking it will hopefully become production-ready in future.

We’re releasing it as open source now in the hope of getting feedback from the community. Also, a few people who heard I was working on this have been bugging me to release it 🙂

The README has more information on how to get started. Please let us know how you get on! Also, I’ll be talking more about Bottled Water at Berlin Buzzwords in June — hope to see you there.

이 블로그 게시물이 마음에 드셨나요? 지금 공유해 주세요.

Confluent 블로그 구독

Introducing KIP-848: The Next Generation of the Consumer Rebalance Protocol

Big news! KIP-848, the next-gen Consumer Rebalance Protocol, is now available in Confluent Cloud! This is a major upgrade for your Kafka clusters, offering faster rebalances and improved stability. Our new blog post dives deep into how KIP-848 functions, making it easy to understand the benefits.

How to Query Apache Kafka® Topics With Natural Language

The users who need access to data stored in Apache Kafka® topics aren’t always experts in technologies like Apache Flink® SQL. This blog shows how users can use natural language processing to have their plain-language questions translated into Flink queries with Confluent Cloud.